Pages

▼

Thursday, February 27, 2020

Wednesday, February 26, 2020

Thursday, February 20, 2020

From the Texas Department of Public Safety: Texas Crime Analysis (2018)

It seems that crime - property crime anyway - is going down in the state.

- Click here for the analysis.

- Click here for the full report.

Crime affects every Texan in some fashion. Togain a measurement of crime trends, Texas participates in the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program. UCR makes possible the analysis of crime trends primarily through the Crime Index.

The Crime Index To track the variations in crime, the UCR data collection program uses a statistical summary tool referred to as the Crime Index. Rather than collecting reports of all crimes that were committed in a particular year, UCR collects the reports of seven index crimes. The crimes in this group are all serious, either by their very nature or because of the frequency with which they occur, and present a common enforcement problem to police agencies.

Crimes within this index can be further categorized as violent crimes, which include murder, rape, robbery and aggravated assault, or as property crimes, which consist of burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft. Although arson and human trafficking are index crimes in that the number of reported offenses is collected, neither is a part of the Crime Index.

During calendar year 2018, there was a reported total of 796,924 index offenses in Texas. The crime volume decreased by 5.4% when compared to 2017. In addition to the above offenses, there were 2,446 cases of arson. There were also 332 human trafficking offenses reported in 2018.

- Click here for the analysis.

- Click here for the full report.

Crime affects every Texan in some fashion. Togain a measurement of crime trends, Texas participates in the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program. UCR makes possible the analysis of crime trends primarily through the Crime Index.

The Crime Index To track the variations in crime, the UCR data collection program uses a statistical summary tool referred to as the Crime Index. Rather than collecting reports of all crimes that were committed in a particular year, UCR collects the reports of seven index crimes. The crimes in this group are all serious, either by their very nature or because of the frequency with which they occur, and present a common enforcement problem to police agencies.

Crimes within this index can be further categorized as violent crimes, which include murder, rape, robbery and aggravated assault, or as property crimes, which consist of burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft. Although arson and human trafficking are index crimes in that the number of reported offenses is collected, neither is a part of the Crime Index.

During calendar year 2018, there was a reported total of 796,924 index offenses in Texas. The crime volume decreased by 5.4% when compared to 2017. In addition to the above offenses, there were 2,446 cases of arson. There were also 332 human trafficking offenses reported in 2018.

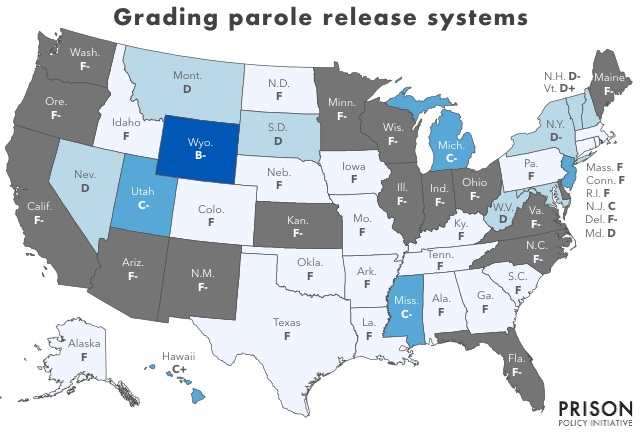

From the Prison Policy Initiative: Grading the parole release systems of all 50 states

For our look at both criminal justice and interest groups.

- Click here for the article.

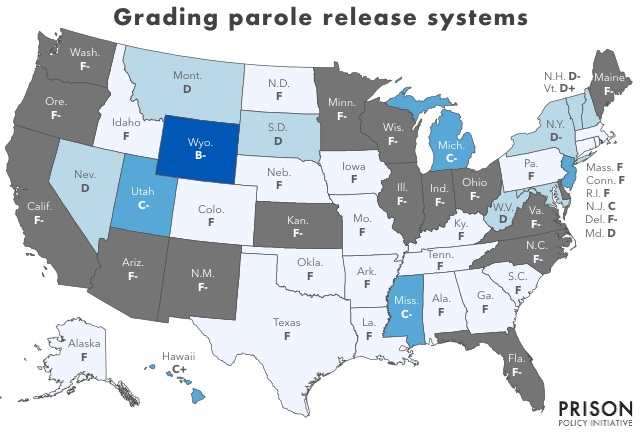

From arrest to sentencing, the process of sending someone to prison in America is full of rules and standards meant to guarantee fairness and predictability. An incredible amount of attention is given to the process, and rightly so. But in sharp contrast, the processes for releasing people from prison are relatively ignored by the public and by the law. State paroling systems vary so much that it is almost impossible to compare them.

Sixteen states have abolished or severely curtailed discretionary parole, and the remaining states range from having a system of presumptive parole — where when certain conditions are met, release on parole is guaranteed — to having policies and practices that make earning release almost impossible.

Parole systems should give every incarcerated person ample opportunity to earn release and have a fair, transparent process for deciding whether to grant it. A growing number of organizations and academics have called for states to adopt policies that would ensure consistency and fairness in how they identify who should receive parole, when those individuals should be reviewed and released, and what parole conditions should be attached to those individuals. In this report, I take the best of those suggestions, assign them point values, and grade the parole systems of each state.

Sadly, most states show lots of room for improvement. Only one state gets a B, five states get Cs, eight states get Ds, and the rest either get an F or an F-.

How we graded and what distinguishes a fair and equitable parole system.

To assess the fairness and equity of each state’s parole system, we looked at five general factors:

Whether a state’s legislature allows the parole board to offer discretionary parole to most people sentenced today; (20 pts.)

The opportunity for the person seeking parole to meet face-to-face with the board members and other factors about witnesses and testimony; (30 pts.)

The principles by which the parole board makes its decisions; (30 pts.)

The degree to which staff help every incarcerated person prepare for their parole hearing; (20 pts.)

The degree to which the parole board is transparent in the way it incorporates evidence-based tools. (20 pts.)

- Click here for the article.

From arrest to sentencing, the process of sending someone to prison in America is full of rules and standards meant to guarantee fairness and predictability. An incredible amount of attention is given to the process, and rightly so. But in sharp contrast, the processes for releasing people from prison are relatively ignored by the public and by the law. State paroling systems vary so much that it is almost impossible to compare them.

Sixteen states have abolished or severely curtailed discretionary parole, and the remaining states range from having a system of presumptive parole — where when certain conditions are met, release on parole is guaranteed — to having policies and practices that make earning release almost impossible.

Parole systems should give every incarcerated person ample opportunity to earn release and have a fair, transparent process for deciding whether to grant it. A growing number of organizations and academics have called for states to adopt policies that would ensure consistency and fairness in how they identify who should receive parole, when those individuals should be reviewed and released, and what parole conditions should be attached to those individuals. In this report, I take the best of those suggestions, assign them point values, and grade the parole systems of each state.

Sadly, most states show lots of room for improvement. Only one state gets a B, five states get Cs, eight states get Ds, and the rest either get an F or an F-.

How we graded and what distinguishes a fair and equitable parole system.

To assess the fairness and equity of each state’s parole system, we looked at five general factors:

Whether a state’s legislature allows the parole board to offer discretionary parole to most people sentenced today; (20 pts.)

The opportunity for the person seeking parole to meet face-to-face with the board members and other factors about witnesses and testimony; (30 pts.)

The principles by which the parole board makes its decisions; (30 pts.)

The degree to which staff help every incarcerated person prepare for their parole hearing; (20 pts.)

The degree to which the parole board is transparent in the way it incorporates evidence-based tools. (20 pts.)

From the Sentencing Project: Private Prisons in the United States

For out look at criminal justice

- Click here for the article.

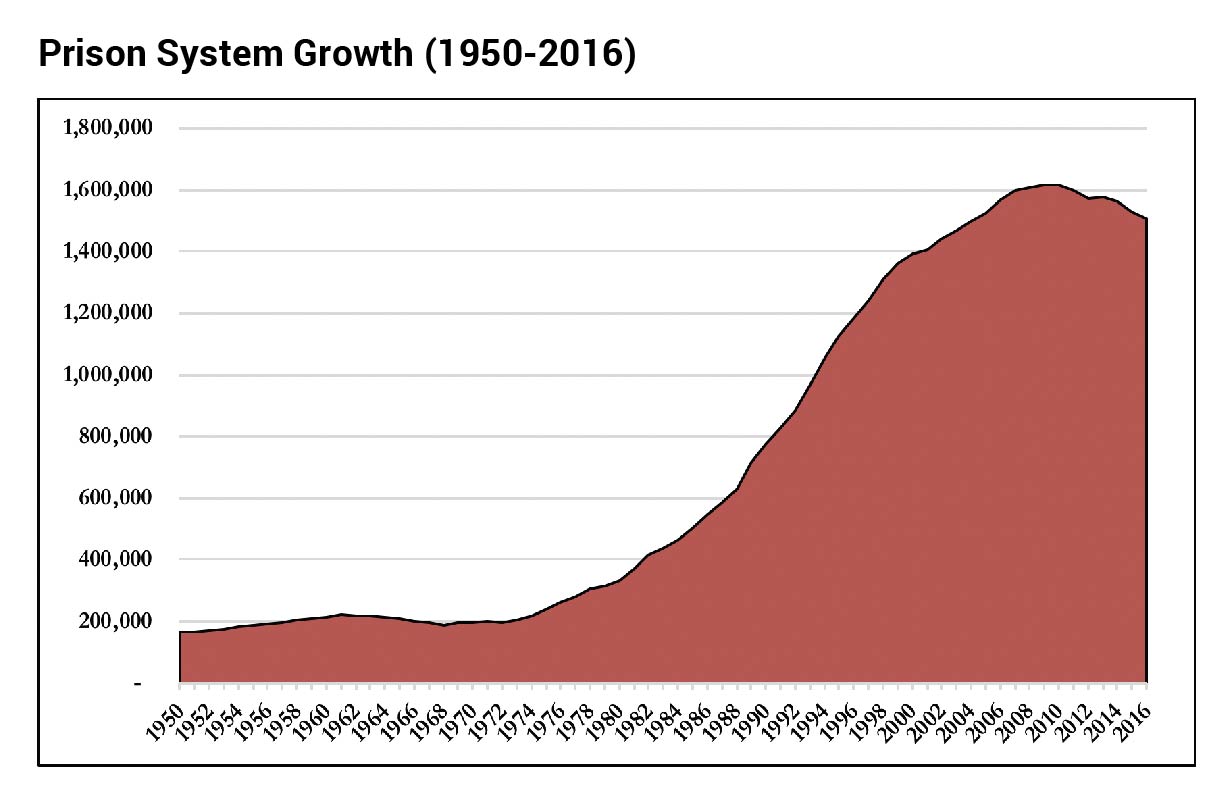

Private prisons in the United States incarcerated 121,718 people in 2017, representing 8.2% of the total state and federal prison population. Since 2000, the number of people housed in private prisons has increased 39%.

However, the private prison population reached its peak in 2012 with 137,220 people. Declines in private prisons’ use make these latest overall population numbers the lowest since 2006 when the population was 113,791.

States show significant variation in their use of private correctional facilities. Indeed, the New Mexico Department of Corrections reports that 53% of its prison population is housed in private facilities, while 22 states do not employ any for-profit prisons. Data compiled by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) and interviews with corrections officials find that in 2017, 28 states and the federal government incarcerated people in private facilities run by corporations including GEO Group, Core Civic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America), and Management and Training Corporation.

Eighteen states with private prison contracts incarcerate more than 500 people in for-profit prisons. Texas, the first state to adopt private prisons in 1985, incarcerated the largest number of people under state jurisdiction, 12,728.

Since 2000, the number of people in private prisons has increased 39.3%, compared to an overall rise in the prison population of 7.8%. In six states the private prison population has more than doubled during this time period: Arizona (479%), Indiana (310%), Ohio (277%), Florida (199%), Tennessee (117%), and Georgia (110%).

- Click here for the article.

Private prisons in the United States incarcerated 121,718 people in 2017, representing 8.2% of the total state and federal prison population. Since 2000, the number of people housed in private prisons has increased 39%.

However, the private prison population reached its peak in 2012 with 137,220 people. Declines in private prisons’ use make these latest overall population numbers the lowest since 2006 when the population was 113,791.

States show significant variation in their use of private correctional facilities. Indeed, the New Mexico Department of Corrections reports that 53% of its prison population is housed in private facilities, while 22 states do not employ any for-profit prisons. Data compiled by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) and interviews with corrections officials find that in 2017, 28 states and the federal government incarcerated people in private facilities run by corporations including GEO Group, Core Civic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America), and Management and Training Corporation.

Eighteen states with private prison contracts incarcerate more than 500 people in for-profit prisons. Texas, the first state to adopt private prisons in 1985, incarcerated the largest number of people under state jurisdiction, 12,728.

Since 2000, the number of people in private prisons has increased 39.3%, compared to an overall rise in the prison population of 7.8%. In six states the private prison population has more than doubled during this time period: Arizona (479%), Indiana (310%), Ohio (277%), Florida (199%), Tennessee (117%), and Georgia (110%).

From the Texas Tribune: As the Texas prison population shrinks, the state is closing two more lockups

A consequence of lighter jail sentences?

- Click here for the article.

Following a declining inmate population and dangerous understaffing in Texas prisons, the state is closing two of its more than 100 lockups.

State Sen. John Whitmire, D-Houston, announced Thursday that the Garza East prison in Beeville and the Jester I Unit in Sugar Land would be closing soon. He said in a statement that all employees at the closing prisons would be offered jobs at nearby facilities, “preventing the loss of any jobs while also addressing understaffing at other units.” A prison spokesperson said the Beeville unit would close in mid-May, and the Sugar Land prison would close this summer.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s executive director, Bryan Collier, said diversion, treatment and education programs, as well as a low rate of people getting sent back to prison, led to the decision.

“This decreasing demand for secure housing and projected stability in the offender population makes possible the decision to reduce state spending through the closure of excess correctional capacity,” Collier said in a statement. “The agency can close these facilities without negatively affecting public safety or causing any loss of jobs.”

- Click here for the article.

Following a declining inmate population and dangerous understaffing in Texas prisons, the state is closing two of its more than 100 lockups.

State Sen. John Whitmire, D-Houston, announced Thursday that the Garza East prison in Beeville and the Jester I Unit in Sugar Land would be closing soon. He said in a statement that all employees at the closing prisons would be offered jobs at nearby facilities, “preventing the loss of any jobs while also addressing understaffing at other units.” A prison spokesperson said the Beeville unit would close in mid-May, and the Sugar Land prison would close this summer.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s executive director, Bryan Collier, said diversion, treatment and education programs, as well as a low rate of people getting sent back to prison, led to the decision.

“This decreasing demand for secure housing and projected stability in the offender population makes possible the decision to reduce state spending through the closure of excess correctional capacity,” Collier said in a statement. “The agency can close these facilities without negatively affecting public safety or causing any loss of jobs.”

Tuesday, February 18, 2020

U.S. Supreme Court cases mentioned in the first five chapters of the Mora - Ruger textbook

This may be incomplete

- Bond v United States

- McCullough v. Maryland

- Wickard v Filburn

- U.S. v Windsor

- Perry v Schwarzenner

- Obergefell v Hodges

- Baker v Carr

- Reynolds v Sims

- Evenwel v. Abbott

- Bush v Vera

- Hunt v. Cromartie

- LULAC v. Perry

- Perry v. Perez

- Shelby County v. Holder

- Hopwood v Texas

Patterson - 2305

- Gideon v Wainwright

- McCullough v Maryland

- Gibbons v Ogden

- Scott v Sanford

- Plessy v Ferguson

- Hammer v Dagenhart

- Lochner v New York

- Schechter Poultry Corp. v United States

- United States v Butler

- Bond v United States

- McCullough v. Maryland

- Wickard v Filburn

- U.S. v Windsor

- Perry v Schwarzenner

- Obergefell v Hodges

- Baker v Carr

- Reynolds v Sims

- Evenwel v. Abbott

- Bush v Vera

- Hunt v. Cromartie

- LULAC v. Perry

- Perry v. Perez

- Shelby County v. Holder

- Hopwood v Texas

Patterson - 2305

- Gideon v Wainwright

- McCullough v Maryland

- Gibbons v Ogden

- Scott v Sanford

- Plessy v Ferguson

- Hammer v Dagenhart

- Lochner v New York

- Schechter Poultry Corp. v United States

- United States v Butler

Company Towns

Looking far ahead to our look at local governments.

- Cheapism: 25 Towns Devastated by Losing a Single Company.

- Oxford: Company Towns in the United States.

- Smithsonian Mag: America's Company Towns, Then and Now.

- VCU: Company Towns: 1880s to 1935.

- Wikipedia: Company Town.

- Wikipedia: Company Town #United States.

- Wikipedia: Lists of Company towns in the United States.

- Cheapism: 25 Towns Devastated by Losing a Single Company.

- Oxford: Company Towns in the United States.

- Smithsonian Mag: America's Company Towns, Then and Now.

- VCU: Company Towns: 1880s to 1935.

- Wikipedia: Company Town.

- Wikipedia: Company Town #United States.

- Wikipedia: Lists of Company towns in the United States.

Thursday, February 13, 2020

Executive Power in the various Texas Constitutions

1845: SEC. 1. The supreme executive power of this State shall be vested in a chief magistrate, who shall be styled the governor of the State of Texas

1861: SECTION 1. The supreme executive power of this State shall be vested in the Chief Magistrate, who shall be styled the Governor of the State of Texas.

1866: SECTION 1. The supreme executive power of this State shall be vested in the Chief Magistrate, who shall be styled the Governor of the State of Texas.

1869: SECTION I. The executive department of the State shall consist of a Chief Magistrate, who shall be styled the Governor, a Lieutenant Governor, Secretary of State, Comptroller of Public Accounts, Treasurer, Commissioner of the General Land Office, Attorney General and Superintendent of Public Instruction.

1876: SECTION 1. The executive department of the State shall consist of a governor, who shall be the chief executive officer of the State, a lieutenant-governor, secretary of State, comptroller of public accounts, treasurer, commissioner of the general land office and attorney general.

As amended in 1995: SECTION 1. The executive department of the State shall consist of a governor, who shall be the chief executive officer of the State, a lieutenant-governor, secretary of State, comptroller of public accounts, treasurer, commissioner of the general land office and attorney general.

1861: SECTION 1. The supreme executive power of this State shall be vested in the Chief Magistrate, who shall be styled the Governor of the State of Texas.

1866: SECTION 1. The supreme executive power of this State shall be vested in the Chief Magistrate, who shall be styled the Governor of the State of Texas.

1869: SECTION I. The executive department of the State shall consist of a Chief Magistrate, who shall be styled the Governor, a Lieutenant Governor, Secretary of State, Comptroller of Public Accounts, Treasurer, Commissioner of the General Land Office, Attorney General and Superintendent of Public Instruction.

1876: SECTION 1. The executive department of the State shall consist of a governor, who shall be the chief executive officer of the State, a lieutenant-governor, secretary of State, comptroller of public accounts, treasurer, commissioner of the general land office and attorney general.

As amended in 1995: SECTION 1. The executive department of the State shall consist of a governor, who shall be the chief executive officer of the State, a lieutenant-governor, secretary of State, comptroller of public accounts, treasurer, commissioner of the general land office and attorney general.

Links - 2/23/20

https://capitol.texas.gov/help/findvoteinfo.aspx

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steven_Avery

https://lrl.texas.gov/legis/ConstAmends/results.cfm?electionDate=Nov%203,%201936

https://www.sunset.texas.gov/reviews-and-reports/agencies

https://www.sunset.texas.gov/impact-sunset-reviews

https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/bpp/index.htm

http://www.harriscountytx.gov/

https://liberationist.org/dividing-people-is-the-best-way-to-lead/

https://www.thefreedictionary.com/Meglomaniac

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steven_Avery

https://lrl.texas.gov/legis/ConstAmends/results.cfm?electionDate=Nov%203,%201936

https://www.sunset.texas.gov/reviews-and-reports/agencies

https://www.sunset.texas.gov/impact-sunset-reviews

https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/bpp/index.htm

http://www.harriscountytx.gov/

https://liberationist.org/dividing-people-is-the-best-way-to-lead/

https://www.thefreedictionary.com/Meglomaniac

From the Texas Tribune 2/13/20

https://www.texastribune.org/2020/02/12/texas-hhs-director-courtney-phillips-leaving-louisiana-job/

https://www.texastribune.org/2020/02/13/houston-mayor-sylvester-turner-endorses-michael-bloomberg-president/

https://www.texastribune.org/2020/02/13/royce-west-democrat-us-senate-flip-texas-coalition/

https://apps.texastribune.org/features/2020/us-senate-primary-voter-guide/?_ga=2.201082734.1104880686.1581607492-736982957.1547583176

https://www.texastribune.org/2020/02/13/houston-mayor-sylvester-turner-endorses-michael-bloomberg-president/

https://www.texastribune.org/2020/02/13/royce-west-democrat-us-senate-flip-texas-coalition/

https://apps.texastribune.org/features/2020/us-senate-primary-voter-guide/?_ga=2.201082734.1104880686.1581607492-736982957.1547583176

Wednesday, February 12, 2020

https://www.infoplease.com/primary-sources/government/anti-federalist-papers/president-military-king

https://slideplayer.com/slide/10796572/

https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/news/politics/2018/09/18/304541/growing-diversity-in-fort-bend-county-may-make-for-tight-contest-in-tx-22/

https://www.harrisvotes.com/SampleBallot/VoterBallot/R/E/0501-REP.pdf

https://www.harrisvotes.com/SampleBallot/VoterBallot/D/E/0501-DEM.pdf

https://frontloading.blogspot.com/

http://www.thegreenpapers.com/P20/

https://slideplayer.com/slide/10796572/

https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/news/politics/2018/09/18/304541/growing-diversity-in-fort-bend-county-may-make-for-tight-contest-in-tx-22/

https://www.harrisvotes.com/SampleBallot/VoterBallot/R/E/0501-REP.pdf

https://www.harrisvotes.com/SampleBallot/VoterBallot/D/E/0501-DEM.pdf

https://frontloading.blogspot.com/

http://www.thegreenpapers.com/P20/

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

For HCC quiz 4

The test will cover both Chapters 4 and 5 in each textbook.

Focus especially in these terms.

2305

due process

establishment

exclusionary rule

imminent lawless action

good faith exemption

prior restraint

right of privacy

selective incorporation

symbolic speech

de-jure discrimination

equal protection clause

reasonable basis test

strict scrutiny

2306

attorney general

board and commissions

budgetary powers

comptroller

impeachment

judicial powers

land commissioner

legislative power

line-item veto

plural executive

secretary of state

Sunset Advisory Commission

appellate courts

grand juries

magistrate functions

onjectivity

partisan election

petit juries

stare decisis

trial courts

Focus especially in these terms.

2305

due process

establishment

exclusionary rule

imminent lawless action

good faith exemption

prior restraint

right of privacy

selective incorporation

symbolic speech

de-jure discrimination

equal protection clause

reasonable basis test

strict scrutiny

2306

attorney general

board and commissions

budgetary powers

comptroller

impeachment

judicial powers

land commissioner

legislative power

line-item veto

plural executive

secretary of state

Sunset Advisory Commission

appellate courts

grand juries

magistrate functions

onjectivity

partisan election

petit juries

stare decisis

trial courts

Regarding Racial Gerrymandering

- Shaw v. Reno.

. . . a landmark United States Supreme Court case argued on April 20, 1993. The ruling was significant in the area of redistricting and racial gerrymandering. The court ruled in a 5-4 decision that redistricting based on race must be held to a standard of strict scrutiny under the equal protection clause. On the other hand, bodies doing redistricting must be conscious of race to the extent that they must ensure compliance with the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The redistricting that occurred after the 2000 census, as required to reflect the population’s changes, was the first nationwide redistricting to apply the results of Shaw v. Reno.

- Hunt v. Cromartie.

. . . a United States Supreme Court case regarding North Carolina's 12th congressional district.[1] In an earlier case, Shaw v. Reno, 517 U.S. 899 (1995), the Supreme Court ruled that the 12th district of North Carolina as drawn was unconstitutional because it was created for the purpose of placing African Americans in one district, thereby constituting illegal racial gerrymandering. The Court ordered the state of North Carolina to redraw the boundaries of the district.

. . . a landmark United States Supreme Court case argued on April 20, 1993. The ruling was significant in the area of redistricting and racial gerrymandering. The court ruled in a 5-4 decision that redistricting based on race must be held to a standard of strict scrutiny under the equal protection clause. On the other hand, bodies doing redistricting must be conscious of race to the extent that they must ensure compliance with the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The redistricting that occurred after the 2000 census, as required to reflect the population’s changes, was the first nationwide redistricting to apply the results of Shaw v. Reno.

- Hunt v. Cromartie.

. . . a United States Supreme Court case regarding North Carolina's 12th congressional district.[1] In an earlier case, Shaw v. Reno, 517 U.S. 899 (1995), the Supreme Court ruled that the 12th district of North Carolina as drawn was unconstitutional because it was created for the purpose of placing African Americans in one district, thereby constituting illegal racial gerrymandering. The Court ordered the state of North Carolina to redraw the boundaries of the district.

Regarding Partisan Gerrymandering

From Ballotpedia:

The phrase partisan gerrymandering refers to the practice of drawing electoral district maps with the intention of favoring one political party over another. On June 27, 2019, the Supreme Court of the United States issued a joint ruling in Rucho v. Common Cause and Lamone v. Benisek, finding that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions that fall beyond the jurisdiction of the federal judiciary.

Notable cases:

- Rucho v. Common Cause

- Lamone v. Benisek

- Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission

- Davis v. Bandemer

The phrase partisan gerrymandering refers to the practice of drawing electoral district maps with the intention of favoring one political party over another. On June 27, 2019, the Supreme Court of the United States issued a joint ruling in Rucho v. Common Cause and Lamone v. Benisek, finding that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions that fall beyond the jurisdiction of the federal judiciary.

Notable cases:

- Rucho v. Common Cause

- Lamone v. Benisek

- Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission

- Davis v. Bandemer

Except as otherwise provided by this code, a political party's nominees in the general election for offices of state and county government and the United States Congress must be nominated by primary election, held as provided by this code, if the party's nominee for governor in the most recent gubernatorial general election received 20 percent or more of the total number of votes received by all candidates for governor in the election.

A political party is entitled to have the names of its nominees placed on the ballot, without qualifying under Subsection (a), in each subsequent general election following a general election in which the party had a nominee for a statewide office who received a number of votes equal to at least five percent of the total number of votes received by all candidates for that office.

A political party is entitled to have the names of its nominees placed on the ballot, without qualifying under Subsection (a), in each subsequent general election following a general election in which the party had a nominee for a statewide office who received a number of votes equal to at least five percent of the total number of votes received by all candidates for that office.

Monday, February 10, 2020

From the Texas Tribune: Analysis: The politics of paying one Texan’s local sales taxes to another Texan’s city

For 2306 - a look at fiscal policy, the sales tax, local government, and the Comptroller.

- Click here for the story.

Sometimes, the best way to challenge something is to notice it.

Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar has proposed a change in the state’s tax rules that could scramble how online sales taxes are collected across the state. Under current law, local taxes on the things Texans buy online go to cities where the sellers are — or say they are. And those tax proceeds are often split by the cities and the companies. In other words, some companies are collecting sales taxes and then getting a portion of them back because they have a deal with a particular city.

If that sounds like a mutation of “Buy Local,” you’re thinking like Hegar.

“Nobody knows about this,” Hegar says. “This is taxation without representation.”

He has proposed sending the tax money from online sales to the buyer’s location, booting up a discussion that might eventually blossom into a reconsideration of how sales taxes work in Texas.

Right now, it’s stirred confusion. It’s also brought some light to a longstanding practice that doesn’t sit right with some voters — especially if you tag it with slogans like “taxation without representation.”

For more: Analysis: A Texas sales tax rule hinges on a question: What’s local?

- Click here for the story.

Sometimes, the best way to challenge something is to notice it.

Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar has proposed a change in the state’s tax rules that could scramble how online sales taxes are collected across the state. Under current law, local taxes on the things Texans buy online go to cities where the sellers are — or say they are. And those tax proceeds are often split by the cities and the companies. In other words, some companies are collecting sales taxes and then getting a portion of them back because they have a deal with a particular city.

If that sounds like a mutation of “Buy Local,” you’re thinking like Hegar.

“Nobody knows about this,” Hegar says. “This is taxation without representation.”

He has proposed sending the tax money from online sales to the buyer’s location, booting up a discussion that might eventually blossom into a reconsideration of how sales taxes work in Texas.

Right now, it’s stirred confusion. It’s also brought some light to a longstanding practice that doesn’t sit right with some voters — especially if you tag it with slogans like “taxation without representation.”

For more: Analysis: A Texas sales tax rule hinges on a question: What’s local?

Links today - 2/10/2020

https://apps.texastribune.org/features/2019/2020-primary-election-ballot/

http://ballotpedia.org/Election_results,_2018_texas

https://apps.texastribune.org/elections/2018/primary-election-results/

https://www.sos.state.tx.us/elections/voter/current.shtml

https://www.sos.state.tx.us/elections/candidates/index.shtml

https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/EL/htm/EL.141.htm

https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/EL/htm/EL.192.htm

https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/art6.asp

http://ballotpedia.org/Election_results,_2018_texas

https://apps.texastribune.org/elections/2018/primary-election-results/

https://www.sos.state.tx.us/elections/voter/current.shtml

https://www.sos.state.tx.us/elections/candidates/index.shtml

https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/EL/htm/EL.141.htm

https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/EL/htm/EL.192.htm

https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/art6.asp

From the Brazoria County Clerk: Elections Division

They are responsible for the actual running of elections in the state, according to state laws.

- Click here for it.

- Click here for it.

From the Texas Tribune: El Paso shooting suspect faces nearly 100 federal charges, including hate crimes

An example of how a criminal activity can involve a high number of offenses, this doesn't even take into consideration state charges.

- Click here for the article.

The man accused of killing 22 people during a mass shooting at a Walmart store in the border city last summer has been charged with nearly 100 federal crimes, John Bash, the U.S. attorney for the Western District of Texas, announced Thursday.

Patrick Crusius, the alleged gunman in the Aug. 3 massacre, already faces state capital murder charges for the racially motivated shooting spree that also wounded dozens.

He is charged federally with 22 counts of hate crimes resulting in death, 23 involving an attempt to kill and 45 charges of firing a weapon in relation to the hate crimes, according to an indictment of Crusius. The U.S. attorney’s office said that upon conviction, prosecutors will seek either the death penalty or life in prison.

Crusius allegedly published a manifesto in which he indicated the crime was motivated by hatred toward Hispanic Americans and immigrants. He also told authorities after he was arrested that he drove 10 hours from his home in Allen to kill Mexicans and ward off what he said was an invasion. Eight of the victims were Mexican nationals.

- Click here for the article.

The man accused of killing 22 people during a mass shooting at a Walmart store in the border city last summer has been charged with nearly 100 federal crimes, John Bash, the U.S. attorney for the Western District of Texas, announced Thursday.

Patrick Crusius, the alleged gunman in the Aug. 3 massacre, already faces state capital murder charges for the racially motivated shooting spree that also wounded dozens.

He is charged federally with 22 counts of hate crimes resulting in death, 23 involving an attempt to kill and 45 charges of firing a weapon in relation to the hate crimes, according to an indictment of Crusius. The U.S. attorney’s office said that upon conviction, prosecutors will seek either the death penalty or life in prison.

Crusius allegedly published a manifesto in which he indicated the crime was motivated by hatred toward Hispanic Americans and immigrants. He also told authorities after he was arrested that he drove 10 hours from his home in Allen to kill Mexicans and ward off what he said was an invasion. Eight of the victims were Mexican nationals.

Carter G. Woodson - The man who brought you Black History Month

- From Wikipedia:

Carter Godwin Woodson (December 19, 1875 – April 3, 1950) was an American historian, author, journalist, and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. He was one of the first scholars to study African-American history. A founder of The Journal of Negro History in 1916, Woodson has been called the "father of black history". In February 1926 he launched the celebration of "Negro History Week", the precursor of Black History Month.

Born in Virginia, the son of former slaves, Woodson had to put off schooling while he worked in the coal mines of West Virginia. He made it to Berea College, becoming a teacher and school administrator. He gained graduate degrees at the University of Chicago and in 1912 was the second African American, after W. E. B. Du Bois, to obtain a PhD degree from Harvard University. Most of Woodson's academic career was spent at Howard University, a historically black university in Washington, D.C., where he eventually served as the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.

Also:

https://time.com/4197928/history-black-history-month/

https://www.loc.gov/law/help/commemorative-observations/african-american.php

https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/01/us/history-of-black-history-month-trnd/index.html

The Federal Register

For future use.

- Click here for the page.

Examples of recent proposed rules:

- National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants: Petroleum Refinery Sector.

- Pipeline Safety: Valve Installation and Minimum Rupture Detection Standards.

- Rules Regarding the Frequency and Notice of Continuing Disability Reviews.

- Click here for the page.

Examples of recent proposed rules:

- National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants: Petroleum Refinery Sector.

- Pipeline Safety: Valve Installation and Minimum Rupture Detection Standards.

- Rules Regarding the Frequency and Notice of Continuing Disability Reviews.

Thursday, February 6, 2020

Texas Constitution, Article 3, Sec. 56. PROHIBITED LOCAL AND SPECIAL LAWS.

(a) The Legislature shall not, except as otherwise provided in this Constitution, pass any local or special law, authorizing:

(1) the creation, extension or impairing of liens;

(2) regulating the affairs of counties, cities, towns, wards or school districts;

(3) changing the names of persons or places;

(4) changing the venue in civil or criminal cases;

(5) authorizing the laying out, opening, altering or maintaining of roads, highways, streets or alleys;

(6) relating to ferries or bridges, or incorporating ferry or bridge companies, except for the erection of bridges crossing streams which form boundaries between this and any other State;

(7) vacating roads, town plats, streets or alleys;

(8) relating to cemeteries, grave-yards or public grounds not of the State;

(9) authorizing the adoption or legitimation of children;

(10) locating or changing county seats;

(11) incorporating cities, towns or villages, or changing their charters;

(12) for the opening and conducting of elections, or fixing or changing the places of voting;

(13) granting divorces;

(14) creating offices, or prescribing the powers and duties of officers, in counties, cities, towns, election or school districts;

(15) changing the law of descent or succession;

(16) regulating the practice or jurisdiction of, or changing the rules of evidence in any judicial proceeding or inquiry before courts, justices of the peace, sheriffs, commissioners, arbitrators or other tribunals, or providing or changing methods for the collection of debts, or the enforcing of judgments, or prescribing the effect of judicial sales of real estate;

(17) regulating the fees, or extending the powers and duties of aldermen, justices of the peace, magistrates or constables;

(18) regulating the management of public schools, the building or repairing of school houses, and the raising of money for such purposes;

(19) fixing the rate of interest;

(20) affecting the estates of minors, or persons under disability;

(21) remitting fines, penalties and forfeitures, and refunding moneys legally paid into the treasury;

(22) exempting property from taxation;

(23) regulating labor, trade, mining and manufacturing;

(24) declaring any named person of age;

(25) extending the time for the assessment or collection of taxes, or otherwise relieving any assessor or collector of taxes from the due performance of his official duties, or his securities from liability;

(26) giving effect to informal or invalid wills or deeds;

(27) summoning or empanelling grand or petit juries;

(28) for limitation of civil or criminal actions;

(29) for incorporating railroads or other works of internal improvements; or

(30) relieving or discharging any person or set of persons from the performance of any public duty or service imposed by general law.

(b) In addition to those laws described by Subsection (a) of this section in all other cases where a general law can be made applicable, no local or special law shall be enacted; provided, that nothing herein contained shall be construed to prohibit the Legislature from passing:

(1) special laws for the preservation of the game and fish of this State in certain localities; and

(2) fence laws applicable to any subdivision of this State or counties as may be needed to meet the wants of the people.

(1) the creation, extension or impairing of liens;

(2) regulating the affairs of counties, cities, towns, wards or school districts;

(3) changing the names of persons or places;

(4) changing the venue in civil or criminal cases;

(5) authorizing the laying out, opening, altering or maintaining of roads, highways, streets or alleys;

(6) relating to ferries or bridges, or incorporating ferry or bridge companies, except for the erection of bridges crossing streams which form boundaries between this and any other State;

(7) vacating roads, town plats, streets or alleys;

(8) relating to cemeteries, grave-yards or public grounds not of the State;

(9) authorizing the adoption or legitimation of children;

(10) locating or changing county seats;

(11) incorporating cities, towns or villages, or changing their charters;

(12) for the opening and conducting of elections, or fixing or changing the places of voting;

(13) granting divorces;

(14) creating offices, or prescribing the powers and duties of officers, in counties, cities, towns, election or school districts;

(15) changing the law of descent or succession;

(16) regulating the practice or jurisdiction of, or changing the rules of evidence in any judicial proceeding or inquiry before courts, justices of the peace, sheriffs, commissioners, arbitrators or other tribunals, or providing or changing methods for the collection of debts, or the enforcing of judgments, or prescribing the effect of judicial sales of real estate;

(17) regulating the fees, or extending the powers and duties of aldermen, justices of the peace, magistrates or constables;

(18) regulating the management of public schools, the building or repairing of school houses, and the raising of money for such purposes;

(19) fixing the rate of interest;

(20) affecting the estates of minors, or persons under disability;

(21) remitting fines, penalties and forfeitures, and refunding moneys legally paid into the treasury;

(22) exempting property from taxation;

(23) regulating labor, trade, mining and manufacturing;

(24) declaring any named person of age;

(25) extending the time for the assessment or collection of taxes, or otherwise relieving any assessor or collector of taxes from the due performance of his official duties, or his securities from liability;

(26) giving effect to informal or invalid wills or deeds;

(27) summoning or empanelling grand or petit juries;

(28) for limitation of civil or criminal actions;

(29) for incorporating railroads or other works of internal improvements; or

(30) relieving or discharging any person or set of persons from the performance of any public duty or service imposed by general law.

(b) In addition to those laws described by Subsection (a) of this section in all other cases where a general law can be made applicable, no local or special law shall be enacted; provided, that nothing herein contained shall be construed to prohibit the Legislature from passing:

(1) special laws for the preservation of the game and fish of this State in certain localities; and

(2) fence laws applicable to any subdivision of this State or counties as may be needed to meet the wants of the people.

Viewed in class 2/6/20

https://www.rrc.state.tx.us/

https://tarltonapps.law.utexas.edu/constitutions/texas1876/a3

https://tmd.texas.gov/office-of-the-adjutant-general

https://www.texasagriculture.gov/Home.aspx

https://www.tcjs.state.tx.us/current-members/

http://www.txrc.texas.gov/agency/commission/former_commissioners.php

https://www.sunset.texas.gov/reviews-and-reports

https://ballotpedia.org/Texas_elections,_2019

https://ballotpedia.org/Texas_elections,_2018

https://tarltonapps.law.utexas.edu/constitutions/texas1876/a3

https://tmd.texas.gov/office-of-the-adjutant-general

https://www.texasagriculture.gov/Home.aspx

https://www.tcjs.state.tx.us/current-members/

http://www.txrc.texas.gov/agency/commission/former_commissioners.php

https://www.sunset.texas.gov/reviews-and-reports

https://ballotpedia.org/Texas_elections,_2019

https://ballotpedia.org/Texas_elections,_2018

Tuesday, February 4, 2020

From Wikipedia: White-Slave Traffic Act of 1910 (AKA - the Mann Act)

The national government starts to become involved in criminal activity.

- Click here for the entry.

The White-Slave Traffic Act, or the Mann Act, is a United States federal law, passed June 25, 1910 (ch. 395, 36 Stat. 825; codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. §§ 2421–2424). It is named after Congressman James Robert Mann of Illinois.

In its original form the act made it a felony to engage in interstate or foreign commerce transport of "any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose". Its primary stated intent was to address prostitution, immorality, and human trafficking, particularly where trafficking was for the purposes of prostitution. It was one of several acts of protective legislation aimed at moral reform during the Progressive Era. In practice, its ambiguous language about "immorality" resulted in it being used to criminalize even consensual sexual behavior between adults. It was amended by Congress in 1978 and again in 1986 to limit its application to transport for the purpose of prostitution or other illegal sexual acts.

For more:

- Congress passes the White Slave Traffic Act, June 25, 1910.

- The ‘White Slavery’ Law That Brought Down Jack Johnson is Still in Effect.

- What is the Mann Act?

- Classification 31: White Slave Traffic Act.

- Click here for the entry.

The White-Slave Traffic Act, or the Mann Act, is a United States federal law, passed June 25, 1910 (ch. 395, 36 Stat. 825; codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. §§ 2421–2424). It is named after Congressman James Robert Mann of Illinois.

In its original form the act made it a felony to engage in interstate or foreign commerce transport of "any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose". Its primary stated intent was to address prostitution, immorality, and human trafficking, particularly where trafficking was for the purposes of prostitution. It was one of several acts of protective legislation aimed at moral reform during the Progressive Era. In practice, its ambiguous language about "immorality" resulted in it being used to criminalize even consensual sexual behavior between adults. It was amended by Congress in 1978 and again in 1986 to limit its application to transport for the purpose of prostitution or other illegal sexual acts.

For more:

- Congress passes the White Slave Traffic Act, June 25, 1910.

- The ‘White Slavery’ Law That Brought Down Jack Johnson is Still in Effect.

- What is the Mann Act?

- Classification 31: White Slave Traffic Act.

From VoteSmart: Government 101: United States Presidential Primary

A primer:

- Click here for it.

The Caucus

Caucuses were the original method for selecting candidates but have decreased in number since the primary was introduced in the early 1900's. In states that hold caucuses a political party announces the date, time, and location of the meeting. Generally any voter registered with the party may attend. At the caucus, delegates are chosen to represent the state's interests at the national party convention. Prospective delegates are identified as favorable to a specific candidate or uncommitted. After discussion and debate an informal vote is taken to determine which delegates should be chosen.

- Click here for it.

The Caucus

Caucuses were the original method for selecting candidates but have decreased in number since the primary was introduced in the early 1900's. In states that hold caucuses a political party announces the date, time, and location of the meeting. Generally any voter registered with the party may attend. At the caucus, delegates are chosen to represent the state's interests at the national party convention. Prospective delegates are identified as favorable to a specific candidate or uncommitted. After discussion and debate an informal vote is taken to determine which delegates should be chosen.

From Vox: Technical difficulties in Iowa caucuses lead to widespread confusion, delayed results

For 2305 and 2306, a story related to parties and elections.

- Click here for the article.

The Iowa caucuses melted down on Monday night after technical difficulties caused significant delays in reporting the results, which have not, as of Tuesday morning, been declared.

A smartphone app, which was reportedly made by a firm called Shadow, appears to be at the center of the confusion. The app was designed to help precinct chairs send the results to the Iowa Democratic Party headquarters, but reports that volunteers were unable to download or properly use the app suggest that this new way of doing things did not go smoothly. A number of volunteers resorted to calling the state party to report results, and many reported being left on hold indefinitely due to busy phone lines.

- Click here for the article.

The Iowa caucuses melted down on Monday night after technical difficulties caused significant delays in reporting the results, which have not, as of Tuesday morning, been declared.

A smartphone app, which was reportedly made by a firm called Shadow, appears to be at the center of the confusion. The app was designed to help precinct chairs send the results to the Iowa Democratic Party headquarters, but reports that volunteers were unable to download or properly use the app suggest that this new way of doing things did not go smoothly. A number of volunteers resorted to calling the state party to report results, and many reported being left on hold indefinitely due to busy phone lines.

Monday, February 3, 2020

From Vox: How the US became the center of global kleptocracy

The reason - according to the author - is federalism.

- Click here for the article.

How US states became masters of the shell game

The biggest single provider of anonymous shell corporations in the world isn’t Panama or the Cayman Islands. It’s not the financial secrecy stalwart Switzerland, or a traditional offshore haven like the Bahamas.

It’s Delaware. And the main reason is federalism.

Thanks to the US’s federal structure, company formation remains overseen at the state level, rather than in Washington.

So if you’re a budding autocrat interested in a bit of easy money laundering, you don’t turn to federal officials in Washington. Instead, you look to state officials in Dover, Cheyenne, or Reno to help construct anonymous shell companies to funnel and clean your illegitimate money.

And these states have taken full advantage. Since there are no regulations in the US requiring that shell companies identify their true owners — known as “beneficial owners” – American states have been under no compunction to try to peel back who may be behind the anonymous shell companies mushrooming across the country.

These states and their constituents are raking in fees — at last check, Delaware made some $1.3 billion annually from its company formation industry — so whenever, say, a human trafficker or extremist network sets up an anonymous company in Wilmington or Laramie or Carson City, they have little incentive to try to figure out who may be behind the companies.

- Click here for the article.

How US states became masters of the shell game

The biggest single provider of anonymous shell corporations in the world isn’t Panama or the Cayman Islands. It’s not the financial secrecy stalwart Switzerland, or a traditional offshore haven like the Bahamas.

It’s Delaware. And the main reason is federalism.

Thanks to the US’s federal structure, company formation remains overseen at the state level, rather than in Washington.

So if you’re a budding autocrat interested in a bit of easy money laundering, you don’t turn to federal officials in Washington. Instead, you look to state officials in Dover, Cheyenne, or Reno to help construct anonymous shell companies to funnel and clean your illegitimate money.

And these states have taken full advantage. Since there are no regulations in the US requiring that shell companies identify their true owners — known as “beneficial owners” – American states have been under no compunction to try to peel back who may be behind the anonymous shell companies mushrooming across the country.

These states and their constituents are raking in fees — at last check, Delaware made some $1.3 billion annually from its company formation industry — so whenever, say, a human trafficker or extremist network sets up an anonymous company in Wilmington or Laramie or Carson City, they have little incentive to try to figure out who may be behind the companies.

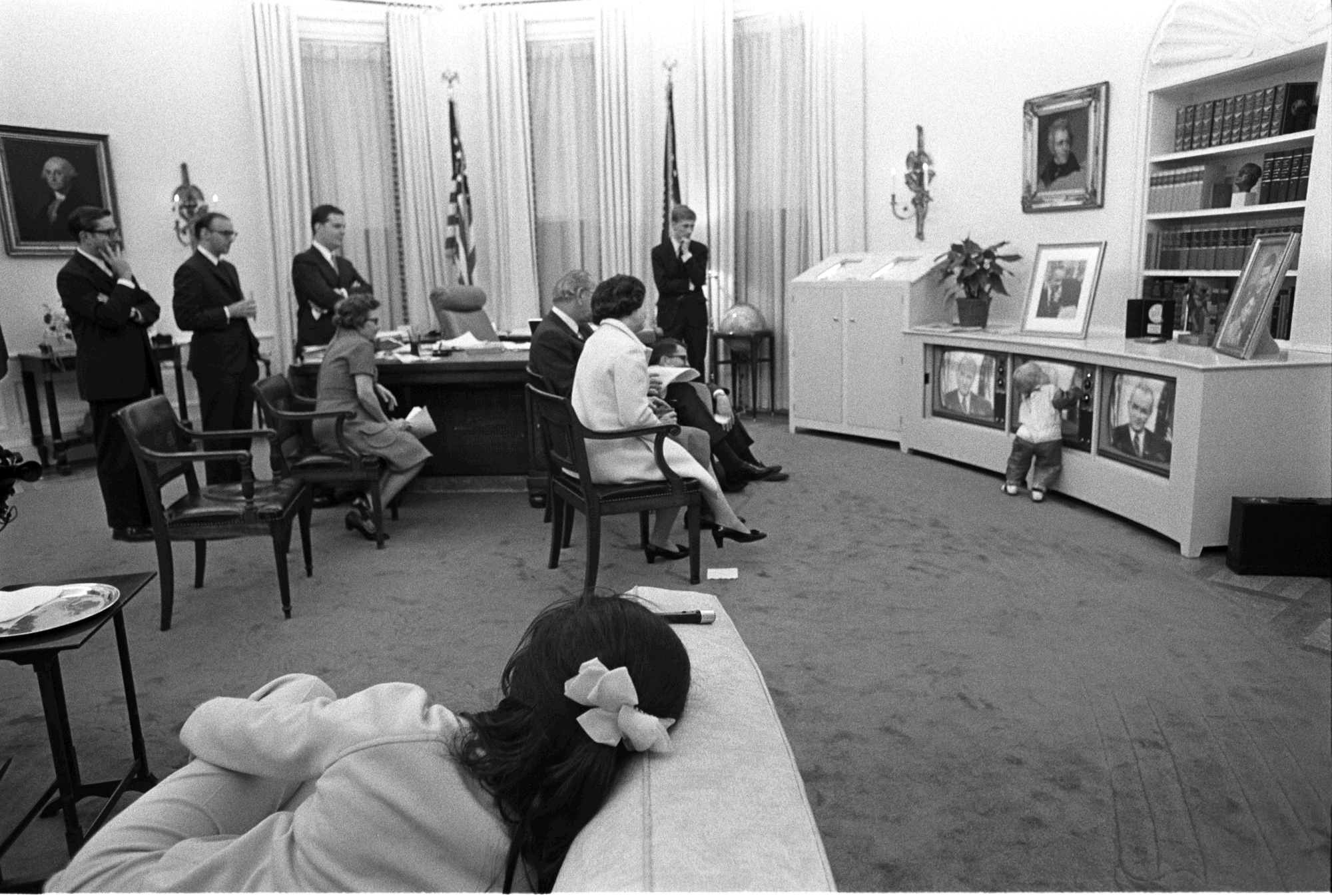

From Lawfare: The Mexican-American War and Constitutional War Powers

Very appropriate for both 2305 - presidential powers - and 2306 - Texas history.

- Click here for the article.

On this day in 1848, the United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending a two-year war. The treaty set the southern Texas border at the Rio Grande and ceded Mexico’s northern provinces (which now include California and large parts of New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah and Colorado) to the United States in return for $15 million. In July of that year, the Senate approved the treaty’s ratification.

In discussions of constitutional war powers, it’s the start of the Mexican-American War that gets most of the attention. Congress’s move in 1845 to annex and grant statehood to Texas probably set the countries on a path toward eventual war. Nevertheless, the main constitutional controversy in most accounts of the war is that President James Polk pretextually manufactured a border crisis to pull Congress into declaring war over American blood spilled in the disputed region between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande (which the United States and Mexico, respectively, regarded as the proper national boundary). Polk had sent Army units into the contested territory, essentially baiting Mexican forces into firing the first shot. Polk had also already drafted a war declaration for Congress before word of the skirmish reached Washington in May 1846. When Polk told Congress that Mexico had killed American troops, his allies rushed the declaration through Congress.

The start of the Mexican-American War is only one of many important constitutional dimensions of the conflict, though, and I don’t think it’s the most interesting. I’m writing about this conflict on the anniversary of its end because its outcome—and the means necessary to achieve it—led to the war’s most noteworthy constitutional precedents.

- Click here for the article.

On this day in 1848, the United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending a two-year war. The treaty set the southern Texas border at the Rio Grande and ceded Mexico’s northern provinces (which now include California and large parts of New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah and Colorado) to the United States in return for $15 million. In July of that year, the Senate approved the treaty’s ratification.

In discussions of constitutional war powers, it’s the start of the Mexican-American War that gets most of the attention. Congress’s move in 1845 to annex and grant statehood to Texas probably set the countries on a path toward eventual war. Nevertheless, the main constitutional controversy in most accounts of the war is that President James Polk pretextually manufactured a border crisis to pull Congress into declaring war over American blood spilled in the disputed region between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande (which the United States and Mexico, respectively, regarded as the proper national boundary). Polk had sent Army units into the contested territory, essentially baiting Mexican forces into firing the first shot. Polk had also already drafted a war declaration for Congress before word of the skirmish reached Washington in May 1846. When Polk told Congress that Mexico had killed American troops, his allies rushed the declaration through Congress.

The start of the Mexican-American War is only one of many important constitutional dimensions of the conflict, though, and I don’t think it’s the most interesting. I’m writing about this conflict on the anniversary of its end because its outcome—and the means necessary to achieve it—led to the war’s most noteworthy constitutional precedents.