Monday, November 19, 2018

What Powers Does the Queen of England Actually Have?

I found this fascinating - compare with the presidents powers, both direct and indirect.

Wednesday, November 14, 2018

From the Dallas Morning News: Native Texans voted for native Texan Beto O'Rourke, transplants went for Ted Cruz, exit poll shows

- Click here for the article.

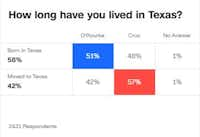

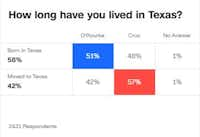

Sen. Ted Cruz and Rep. Beto O’Rourke fought during the Senate race over who was more Texan. It turns out that native Texan voters think O’Rourke is.

A CNN exit poll showed that O'Rourke beat Cruz among native Texans, 51 percent to 48 percent. In contrast, 57 percent of people who had moved to Texas said they voted for Cruz, compared to 42 percent who voted for O'Rourke.

Cruz prevailed Tuesday night, beating his opponent by just 2.6 percentage points. It's the closest Senate race in Texas since 1978.

This midterm race caught everyone’s attention. O'Rourke, a Democrat and native of El Paso, challenged the Republican incumbent from Houston who was coming off a presidential run. Cruz proudly calls Houston home, even though questions were raised when he ran for president about his family living in Canada for the first five years of his life.

While lawmakers in Texas have talked about the wave of Californians moving to Texas and wanting to turn the state blue, data reported by the Texas Tribune in 2013 suggested these people moving to Texas aligned with conservative values more than liberal values.

- Complete Exit Polls.

Sen. Ted Cruz and Rep. Beto O’Rourke fought during the Senate race over who was more Texan. It turns out that native Texan voters think O’Rourke is.

A CNN exit poll showed that O'Rourke beat Cruz among native Texans, 51 percent to 48 percent. In contrast, 57 percent of people who had moved to Texas said they voted for Cruz, compared to 42 percent who voted for O'Rourke.

Cruz prevailed Tuesday night, beating his opponent by just 2.6 percentage points. It's the closest Senate race in Texas since 1978.

This midterm race caught everyone’s attention. O'Rourke, a Democrat and native of El Paso, challenged the Republican incumbent from Houston who was coming off a presidential run. Cruz proudly calls Houston home, even though questions were raised when he ran for president about his family living in Canada for the first five years of his life.

While lawmakers in Texas have talked about the wave of Californians moving to Texas and wanting to turn the state blue, data reported by the Texas Tribune in 2013 suggested these people moving to Texas aligned with conservative values more than liberal values.

- Complete Exit Polls.

From Lawfare: Foreign Election Interference in the Founding Era

Interesting history.

- Click here for the article.

In the fall of 1794, American delegates signed the Jay Treaty with Great Britain in an attempt to resolve outstanding trade and territorial issues, while keeping the fledgling republic from being drawn into ongoing hostilities between Britain and France. The Directory, the five-member committee governing France at the time, viewed the treaty as an abandonment of prior French-U.S. commitments. In June of 1795, as President George Washington debated moving the treaty to the Senate for approval, the Directory sent a new minister to the United States with specific instructions identifying the Jay Treaty as France’s “foremost grievance” against the country.

French intervention in American politics was not without precedent. As early as the Revolutionary War, French agents had routinely used bribery and other pressures to influence the Continental Congress. One particularly notorious incident occurred in 1793 when war broke out between Britain and France. Without first consulting the president, the French minister to the United States, Edmond-Charles Genet, began commissioning privateers out of Charleston, South Carolina to fight the British. The “Genet Affair” divided Washington’s cabinet, especially between Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson who favored France and Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton who favored neutrality. In the end, Washington issued a neutrality policy and his administration demanded Genet’s recall.

In 1795, the minister, Pierre-Auguste Adet, began bribing senators to derail the Jay Treaty, but the French government’s lack of funds hampered these efforts, and the Senate narrowly approved it. Using his diplomatic status to obtain a copy of the Treaty text, Adet had it published. The release provoked a public outcry throughout United States and sharply divided Americans.

- Click here for the article.

In the fall of 1794, American delegates signed the Jay Treaty with Great Britain in an attempt to resolve outstanding trade and territorial issues, while keeping the fledgling republic from being drawn into ongoing hostilities between Britain and France. The Directory, the five-member committee governing France at the time, viewed the treaty as an abandonment of prior French-U.S. commitments. In June of 1795, as President George Washington debated moving the treaty to the Senate for approval, the Directory sent a new minister to the United States with specific instructions identifying the Jay Treaty as France’s “foremost grievance” against the country.

French intervention in American politics was not without precedent. As early as the Revolutionary War, French agents had routinely used bribery and other pressures to influence the Continental Congress. One particularly notorious incident occurred in 1793 when war broke out between Britain and France. Without first consulting the president, the French minister to the United States, Edmond-Charles Genet, began commissioning privateers out of Charleston, South Carolina to fight the British. The “Genet Affair” divided Washington’s cabinet, especially between Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson who favored France and Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton who favored neutrality. In the end, Washington issued a neutrality policy and his administration demanded Genet’s recall.

In 1795, the minister, Pierre-Auguste Adet, began bribing senators to derail the Jay Treaty, but the French government’s lack of funds hampered these efforts, and the Senate narrowly approved it. Using his diplomatic status to obtain a copy of the Treaty text, Adet had it published. The release provoked a public outcry throughout United States and sharply divided Americans.

A list of people found guilty of treason in the US

We looked this over in 2305 yesterday after wondering if the narrow definition of treason in the Constitution made it difficult to enforce. This is from Wikipedia, so I;m not sure if it is comprehensive, but if it is, then apparently it is difficult.

Philip Vigol and John Mitchell, convicted of treason and sentenced to hanging; pardoned by George Washington; see Whiskey Rebellion.

John Fries, the leader of Fries' Rebellion, convicted of treason in 1800 along with two accomplices, and pardoned that same year by John Adams.

Governor Thomas Dorr 1844, convicted of treason against the state of Rhode Island; see Dorr Rebellion; released in 1845; civil rights restored in 1851; verdict annulled in 1854.

John Brown, convicted of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1859 and executed for attempting to organize armed resistance to slavery.

Aaron Dwight Stevens, took part in John Brown's raid and was executed in 1860 for treason against Virginia.

William Bruce Mumford, convicted of treason and hanged in 1862 for tearing down a United States flag during the American Civil War.

Walter Allen was convicted of treason on September 16, 1922 for taking part in the 1921 Miner's March with the coal companies and the US Army on Blair Mountain, West Virginia. He was sentenced to 10 years and fined. During his appeal to the Supreme Court he disappeared while out on bail. United Mineworkers of America leader William Blizzard was acquitted of the charge of treason by the jury on May 25, 1922.[12]

Martin James Monti, United States Army Air Forces pilot, convicted of treason for defecting to the Waffen SS in 1944. He was paroled in 1960.

Robert Henry Best, convicted of treason on April 16, 1948 and served a life sentence.

Iva Toguri D'Aquino, who is frequently identified by the name "Tokyo Rose", convicted 1949. Subsequently, pardoned by President Gerald Ford.

Mildred Gillars, also known as "Axis Sally", convicted of treason on March 8, 1949; served 12 years of a 10- to 30-year prison sentence.

Tomoya Kawakita, sentenced to death for treason in 1952, but eventually released by President John F. Kennedy to be deported to Japan.

Philip Vigol and John Mitchell, convicted of treason and sentenced to hanging; pardoned by George Washington; see Whiskey Rebellion.

John Fries, the leader of Fries' Rebellion, convicted of treason in 1800 along with two accomplices, and pardoned that same year by John Adams.

Governor Thomas Dorr 1844, convicted of treason against the state of Rhode Island; see Dorr Rebellion; released in 1845; civil rights restored in 1851; verdict annulled in 1854.

John Brown, convicted of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1859 and executed for attempting to organize armed resistance to slavery.

Aaron Dwight Stevens, took part in John Brown's raid and was executed in 1860 for treason against Virginia.

William Bruce Mumford, convicted of treason and hanged in 1862 for tearing down a United States flag during the American Civil War.

Walter Allen was convicted of treason on September 16, 1922 for taking part in the 1921 Miner's March with the coal companies and the US Army on Blair Mountain, West Virginia. He was sentenced to 10 years and fined. During his appeal to the Supreme Court he disappeared while out on bail. United Mineworkers of America leader William Blizzard was acquitted of the charge of treason by the jury on May 25, 1922.[12]

Martin James Monti, United States Army Air Forces pilot, convicted of treason for defecting to the Waffen SS in 1944. He was paroled in 1960.

Robert Henry Best, convicted of treason on April 16, 1948 and served a life sentence.

Iva Toguri D'Aquino, who is frequently identified by the name "Tokyo Rose", convicted 1949. Subsequently, pardoned by President Gerald Ford.

Mildred Gillars, also known as "Axis Sally", convicted of treason on March 8, 1949; served 12 years of a 10- to 30-year prison sentence.

Tomoya Kawakita, sentenced to death for treason in 1952, but eventually released by President John F. Kennedy to be deported to Japan.

‘Even the Mafia Was More Circumspect’ Glenn Shankle goes from regulator to lobbyist.

A look at the revolving door in Texas.

- Click here for the article.

The revolving door between government and the private sector is a time-worn tradition in Texas. But here’s a case that on its bare facts is particularly egregious.

In January, six months after stepping down as the executive director of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, Glenn Shankle signed on as a lobbyist for Waste Control Specialists, the company recently licensed by TCEQ to build a massive radioactive waste dump in West Texas. His lobby contract is worth between $100,000 and $150,000, according to the Texas Ethics Commission.

When Shankle left TCEQ in June 2008, the agency was readying, per Shankle’s orders, two licenses authorizing Waste Control to bury millions of cubic feet of radioactive waste. The four-year license review process had been one of the most time-consuming and contentious in agency history.

Shankle’s own technical staff, geologists and engineers had concluded definitively that the dump could not legally be permitted. An Aug. 14, 2007, memo drafted by two geologists and two engineers bluntly stated that the landfill’s proximity to two aquifers made it “highly likely” that radioactive waste would leak into the groundwater. The site, they wrote, “cannot be improved through special license conditions.” They recommended denying the license. With little explanation, Shankle overruled them. His only sop to the staff were license conditions requiring additional studies before construction.

Amazingly, Shankle said in a brief telephone interview yesterday—one of the few times he has ever spoken to the press—that he had never heard of any of this.

“I was not aware of that,” Shankle said of his own technical staff’s recommendations. If true, that’s stunning. According to the Houston Chronicle:

When WCS President Rodney Baltzer learned of the [August 14] memo, he immediately sought out meetings with the agency’s executive director, Glenn Shankle, who decided in December [2007] to begin drafting the license.

In fact, records from TCEQ, previously discussed in the Observer, show that during the time period after the staff’s recommendation, Shankle was frequently meeting with Waste Control officials, attorneys and lobbyists. Waste Control is owned by Harold Simmons, the Dallas billionaire and major Republican donor who helped bankroll Swift Boat ads attacking John Kerry in 2004 and television ads in 2008 linking Barack Obama to Bill Ayers.

For more:

- Shankle to take director position at TCEQ.- Lawyer for industry played key role establishing Texas environmental laws.

- Click here for the article.

The revolving door between government and the private sector is a time-worn tradition in Texas. But here’s a case that on its bare facts is particularly egregious.

In January, six months after stepping down as the executive director of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, Glenn Shankle signed on as a lobbyist for Waste Control Specialists, the company recently licensed by TCEQ to build a massive radioactive waste dump in West Texas. His lobby contract is worth between $100,000 and $150,000, according to the Texas Ethics Commission.

When Shankle left TCEQ in June 2008, the agency was readying, per Shankle’s orders, two licenses authorizing Waste Control to bury millions of cubic feet of radioactive waste. The four-year license review process had been one of the most time-consuming and contentious in agency history.

Shankle’s own technical staff, geologists and engineers had concluded definitively that the dump could not legally be permitted. An Aug. 14, 2007, memo drafted by two geologists and two engineers bluntly stated that the landfill’s proximity to two aquifers made it “highly likely” that radioactive waste would leak into the groundwater. The site, they wrote, “cannot be improved through special license conditions.” They recommended denying the license. With little explanation, Shankle overruled them. His only sop to the staff were license conditions requiring additional studies before construction.

Amazingly, Shankle said in a brief telephone interview yesterday—one of the few times he has ever spoken to the press—that he had never heard of any of this.

“I was not aware of that,” Shankle said of his own technical staff’s recommendations. If true, that’s stunning. According to the Houston Chronicle:

When WCS President Rodney Baltzer learned of the [August 14] memo, he immediately sought out meetings with the agency’s executive director, Glenn Shankle, who decided in December [2007] to begin drafting the license.

In fact, records from TCEQ, previously discussed in the Observer, show that during the time period after the staff’s recommendation, Shankle was frequently meeting with Waste Control officials, attorneys and lobbyists. Waste Control is owned by Harold Simmons, the Dallas billionaire and major Republican donor who helped bankroll Swift Boat ads attacking John Kerry in 2004 and television ads in 2008 linking Barack Obama to Bill Ayers.

For more:

- Shankle to take director position at TCEQ.- Lawyer for industry played key role establishing Texas environmental laws.

The Week: Sorry, liberals: The Senate 'popular vote' doesn't matter

A nice reminder about the nature of the Senate - as well as the low level of knowledge people have about our constitutional system.

- Click here for the article.

While constitutionally irrelevant, popular votes for the office of the president and for the House make sense conceptually. We look to the popular vote in presidential elections because, in every race from 1892 until 2000, the candidate who won it also went on to take the Electoral College. It seemed like a solid predictor of who would become the next president of the United States.

So why isn't the popular vote worth noting in Senate races? Because it doesn't even measure anything meaningful. Unlike the House, only a third of Senate seats are up in any given cycle. This year, Democrats were defending 26 of those to the Republicans' nine, so it stands to reason they would get a lot of votes. California, the most populous state, will increasingly have Senate elections where no Republicans are even on the ballot.

"While Democrats lost seats on Tuesday night, they actually won most of the races that were held — at least 22 of the 35 seats, and possibly a couple more," The Washington Post's Aaron Blake explains. "That's 63 percent or more of the seats, despite winning just 55 percent of the vote."

- Click here for the article.

While constitutionally irrelevant, popular votes for the office of the president and for the House make sense conceptually. We look to the popular vote in presidential elections because, in every race from 1892 until 2000, the candidate who won it also went on to take the Electoral College. It seemed like a solid predictor of who would become the next president of the United States.

So why isn't the popular vote worth noting in Senate races? Because it doesn't even measure anything meaningful. Unlike the House, only a third of Senate seats are up in any given cycle. This year, Democrats were defending 26 of those to the Republicans' nine, so it stands to reason they would get a lot of votes. California, the most populous state, will increasingly have Senate elections where no Republicans are even on the ballot.

"While Democrats lost seats on Tuesday night, they actually won most of the races that were held — at least 22 of the 35 seats, and possibly a couple more," The Washington Post's Aaron Blake explains. "That's 63 percent or more of the seats, despite winning just 55 percent of the vote."

Wednesday, November 7, 2018

Election commentary from the Texas Tribune

- Are Texas suburbs slipping away from Republicans?

By the end of Election Day, the political maps of the state’s suburban and swing counties had a peculiar blue tint.

The blue washed over the Dallas-Fort Worth area and crept up on suburban counties in North Texas. It spread from Houston — in a county that was once a political battleground — and crested over some of its suburban communities. And it swept through the Interstate 35 corridor from Travis County to its neighbors to the north and south.

Counties that haven’t voted for a Democrat in decades turned out for Beto O’Rourke in his unsuccessful bid to unseat U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz, and he picked up enough support in ruby red Republican counties to force Cruz into single-digit wins.

It could all be a blip — a year of Democratic enthusiasm spurred by a shiny candidate or vitriol toward President Donald Trump. But with margins narrowing over time in some of the GOP’s longtime strongholds, Tuesday night's results suggest that the Republican firewall in the suburbs could be cracking.

- In Dallas County, Republican gerrymandering backfired in 2018.

The Republican losses in Dallas County are as much a product of the 2018 blue waveas they are of 2011 redistricting, when the GOP was forced to confront a politically inconvenient demographic reality. The 2010 census showed that people of color, who tend to support Democrats, were behind all of Dallas County’s growth in the last decade. Meanwhile, the county’s white population decreased by more than 198,000 people.

On top of that, Dallas’ growth relative to the state as a whole meant that the number of House seats in the county needed to drop from 16 to 14. Mapdrawers knew that those two seats would have to be Republican-held seats because the Dallas County districts represented by Democrats — and mostly made up by Hispanic and black voters — were protected by the Voting Rights Act.

As far as Democrats and redistricting experts are concerned, Republicans could have opted to create a new “opportunity district” for the county’s growing population of color. That would’ve reduced the number of voters of color in Republican districts, giving the GOP more of a cushion through the decade, but it would have also likely added another seat to the Democrats’ column.

- In Texas, the "Rainbow Wave" outpaces the blue one.

Fourteen of the 35 gay, bisexual and transgender candidates who ran for office in Texas during the midterms claimed victory Tuesday night — a 40 percent success rate in deep-red Texas — and national and state activists say they’re confident this election cycle carved a path for a future “rainbow wave” in Texas.

The historic number of Texas candidates who ran for offices from governor down to city council positions joined a record-shattering rank of more than 400 LGBTQ individuals on national midterm ballots this year.|

- Texas House Speaker Joe Straus: Texas and the Republican Party are “moving in opposite directions”

Republicans in the Texas House were dealt a big blow Tuesday night, losing 12 seatsto Democrats and two in the Texas Senate.

Joe Straus, the Republican who has presided over the House for nearly a decade, said that's because win-at-all-cost politics may be effective at the state level, but "it creates carnage down-ballot in a changing state where a Republican Party and the state of Texas are moving in opposite directions."

The "small issues" that were popular among Republican primary voters didn't resonate in November, he said.

- As Democrats seize U.S. House control, Texas congressional delegation set to lose clout in Washington.

The Texas congressional delegation is poised to lose significant clout on Capitol Hill after the Democrats on Tuesday took control of the U.S. House and Texas voters elected nine new representatives — one-quarter of the state's 36 members.

All told, Texas Republicans will lose seven committee chairmanships. Three of those — Mac Thornberry of Clarendon, chairman of the Armed Services Committee; Mike Conaway of Midland, chairman of the Agriculture Committee; and Kevin Brady of The Woodland, chairman of the Ways and Means Committee — won re-election Tuesday and are likely to become ranking members on those committees.

Lamar Smith of San Antonio and Jeb Hensarling of Dallas announced earlier this year they would not seek re-election, ending their tenures as chairmen of the Science, Space & Technology and Financial Services committees, respectively.They're being replaced by fellow Republicans — Chip Roy in Smith's seat and Lance Gooden in Hensarling's — who both will begin their congressional careers low in the hierarchy of their caucus.

- After losing election, Houston juvenile court judge releases defendants en masse.

On Tuesday, Harris County Family Judge Glenn Devlin lost his re-election bid to Democrat Natalia Oakes. On Wednesday, he showed up for work in the 313th District Court and began releasing virtually all of the juvenile defenders who had detention hearings before him, according to the Houston Chronicle.

The Chronicle reports that Devlin simply asked the defendants whether they planned to kill anyone, then released nearly all of them from detention. Under state law, juveniles who are locked up while their cases are pending are required to have a hearing every 10 business days so a judge can decide whether they should stay in detention. It's not clear how many defendants Devlin released Wednesday, but the Chronicle reports that the judge reset all of their cases for Jan. 4 — the day Oakes takes the gavel in the 313th.

By the end of Election Day, the political maps of the state’s suburban and swing counties had a peculiar blue tint.

The blue washed over the Dallas-Fort Worth area and crept up on suburban counties in North Texas. It spread from Houston — in a county that was once a political battleground — and crested over some of its suburban communities. And it swept through the Interstate 35 corridor from Travis County to its neighbors to the north and south.

Counties that haven’t voted for a Democrat in decades turned out for Beto O’Rourke in his unsuccessful bid to unseat U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz, and he picked up enough support in ruby red Republican counties to force Cruz into single-digit wins.

It could all be a blip — a year of Democratic enthusiasm spurred by a shiny candidate or vitriol toward President Donald Trump. But with margins narrowing over time in some of the GOP’s longtime strongholds, Tuesday night's results suggest that the Republican firewall in the suburbs could be cracking.

- In Dallas County, Republican gerrymandering backfired in 2018.

The Republican losses in Dallas County are as much a product of the 2018 blue waveas they are of 2011 redistricting, when the GOP was forced to confront a politically inconvenient demographic reality. The 2010 census showed that people of color, who tend to support Democrats, were behind all of Dallas County’s growth in the last decade. Meanwhile, the county’s white population decreased by more than 198,000 people.

On top of that, Dallas’ growth relative to the state as a whole meant that the number of House seats in the county needed to drop from 16 to 14. Mapdrawers knew that those two seats would have to be Republican-held seats because the Dallas County districts represented by Democrats — and mostly made up by Hispanic and black voters — were protected by the Voting Rights Act.

As far as Democrats and redistricting experts are concerned, Republicans could have opted to create a new “opportunity district” for the county’s growing population of color. That would’ve reduced the number of voters of color in Republican districts, giving the GOP more of a cushion through the decade, but it would have also likely added another seat to the Democrats’ column.

- In Texas, the "Rainbow Wave" outpaces the blue one.

Fourteen of the 35 gay, bisexual and transgender candidates who ran for office in Texas during the midterms claimed victory Tuesday night — a 40 percent success rate in deep-red Texas — and national and state activists say they’re confident this election cycle carved a path for a future “rainbow wave” in Texas.

The historic number of Texas candidates who ran for offices from governor down to city council positions joined a record-shattering rank of more than 400 LGBTQ individuals on national midterm ballots this year.|

- Texas House Speaker Joe Straus: Texas and the Republican Party are “moving in opposite directions”

Republicans in the Texas House were dealt a big blow Tuesday night, losing 12 seatsto Democrats and two in the Texas Senate.

Joe Straus, the Republican who has presided over the House for nearly a decade, said that's because win-at-all-cost politics may be effective at the state level, but "it creates carnage down-ballot in a changing state where a Republican Party and the state of Texas are moving in opposite directions."

The "small issues" that were popular among Republican primary voters didn't resonate in November, he said.

- As Democrats seize U.S. House control, Texas congressional delegation set to lose clout in Washington.

The Texas congressional delegation is poised to lose significant clout on Capitol Hill after the Democrats on Tuesday took control of the U.S. House and Texas voters elected nine new representatives — one-quarter of the state's 36 members.

All told, Texas Republicans will lose seven committee chairmanships. Three of those — Mac Thornberry of Clarendon, chairman of the Armed Services Committee; Mike Conaway of Midland, chairman of the Agriculture Committee; and Kevin Brady of The Woodland, chairman of the Ways and Means Committee — won re-election Tuesday and are likely to become ranking members on those committees.

Lamar Smith of San Antonio and Jeb Hensarling of Dallas announced earlier this year they would not seek re-election, ending their tenures as chairmen of the Science, Space & Technology and Financial Services committees, respectively.They're being replaced by fellow Republicans — Chip Roy in Smith's seat and Lance Gooden in Hensarling's — who both will begin their congressional careers low in the hierarchy of their caucus.

- After losing election, Houston juvenile court judge releases defendants en masse.

On Tuesday, Harris County Family Judge Glenn Devlin lost his re-election bid to Democrat Natalia Oakes. On Wednesday, he showed up for work in the 313th District Court and began releasing virtually all of the juvenile defenders who had detention hearings before him, according to the Houston Chronicle.

The Chronicle reports that Devlin simply asked the defendants whether they planned to kill anyone, then released nearly all of them from detention. Under state law, juveniles who are locked up while their cases are pending are required to have a hearing every 10 business days so a judge can decide whether they should stay in detention. It's not clear how many defendants Devlin released Wednesday, but the Chronicle reports that the judge reset all of their cases for Jan. 4 — the day Oakes takes the gavel in the 313th.

Tuesday, November 6, 2018

From the Constitution Center: THE PRESIDENT'S EXCLUSIVE POWER TO DIRECT MILITARY OPERATIONS

A look at the conflict involving the president's military powers

- Click here for the article.

If the United States undertakes military operations, either by authorization from Congress or under the President’s independent powers, the Constitution makes the President Commander in Chief of all U.S. military forces, and Congress cannot give command to any other person. But can Congress itself direct how the President exercises that command by requiring or prohibiting certain military actions?

Scholarly opinion is sharply divided on this question. One view, principally associated with Professor John Yoo, holds that attempts by Congress to control the military contrary to the President’s desires infringe the Commander in Chief Clause by in effect depriving the President of the full ability to give commands. An opposing view, developed by Professor Saikrishna Prakash in a series of articles and an important 2015 book on executive power, sees Congress as having complete power over the military through various clauses of Article I, Section 8, with the President’s substantive command authority operating only where Congress has not provided specific direction.

Both views seem to overstate. Contrary to the first view, the Constitution expressly gives Congress significant power over the military. Most notably, Congress has power to “make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces.” Nothing in the Constitution requires these “Rules” to be consistent with the President’s desires (although of course the President can resist them using the veto power). Further, Congress has a long history of regulating the military, including the articles of war (precursor of the modern Uniform Code of Military Justice) enacted in the immediate post-ratification period. Thus, for example, rules regarding how prisoners are to be treated, whether civilians may be targeted and how intelligence may be gathered by the military seem fully within Congress’s enumerated power. If the President’s Commander in Chief power overrode these rules, the Government-and-Regulation Clause would seem almost meaningless. In addition, Congress’s power to declare war likely includes power to set wartime goals and to limit a war’s scope. Prior to the Constitution, other nations routinely issued goal-setting declarations and fought limited wars. And Congress’s power to define the scope of a war seems confirmed by Congress’s statutory limits on the 1798 Quasi-War with France and by the Supreme Court’s approval of those limits in Bas v. Tingy (1800) and Little v. Barreme (1804).

However, contrary to the second view, the Constitution’s enumeration of Congress’s specific military powers indicates that Congress does not have plenary authority over military operations. In particular, although Congress can make general rules regarding military conduct and can define wartime objectives, it lacks enumerated power to direct battlefield operations—a point demonstrated by examining Congress’s powers under the Articles of Confederation.

In contrast to the Constitution, the Articles gave Congress the powers of “making rules for the government and regulation of the said land and naval forces, and of directing their operations” (emphasis added). The former power is carried over directly into the Constitution’s list of congressional powers, but the latter is not. This strongly suggests that Congress’s Government-and-Regulation power does not include power to “direct [military] operations.”

- Click here for the article.

If the United States undertakes military operations, either by authorization from Congress or under the President’s independent powers, the Constitution makes the President Commander in Chief of all U.S. military forces, and Congress cannot give command to any other person. But can Congress itself direct how the President exercises that command by requiring or prohibiting certain military actions?

Scholarly opinion is sharply divided on this question. One view, principally associated with Professor John Yoo, holds that attempts by Congress to control the military contrary to the President’s desires infringe the Commander in Chief Clause by in effect depriving the President of the full ability to give commands. An opposing view, developed by Professor Saikrishna Prakash in a series of articles and an important 2015 book on executive power, sees Congress as having complete power over the military through various clauses of Article I, Section 8, with the President’s substantive command authority operating only where Congress has not provided specific direction.

Both views seem to overstate. Contrary to the first view, the Constitution expressly gives Congress significant power over the military. Most notably, Congress has power to “make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces.” Nothing in the Constitution requires these “Rules” to be consistent with the President’s desires (although of course the President can resist them using the veto power). Further, Congress has a long history of regulating the military, including the articles of war (precursor of the modern Uniform Code of Military Justice) enacted in the immediate post-ratification period. Thus, for example, rules regarding how prisoners are to be treated, whether civilians may be targeted and how intelligence may be gathered by the military seem fully within Congress’s enumerated power. If the President’s Commander in Chief power overrode these rules, the Government-and-Regulation Clause would seem almost meaningless. In addition, Congress’s power to declare war likely includes power to set wartime goals and to limit a war’s scope. Prior to the Constitution, other nations routinely issued goal-setting declarations and fought limited wars. And Congress’s power to define the scope of a war seems confirmed by Congress’s statutory limits on the 1798 Quasi-War with France and by the Supreme Court’s approval of those limits in Bas v. Tingy (1800) and Little v. Barreme (1804).

However, contrary to the second view, the Constitution’s enumeration of Congress’s specific military powers indicates that Congress does not have plenary authority over military operations. In particular, although Congress can make general rules regarding military conduct and can define wartime objectives, it lacks enumerated power to direct battlefield operations—a point demonstrated by examining Congress’s powers under the Articles of Confederation.

In contrast to the Constitution, the Articles gave Congress the powers of “making rules for the government and regulation of the said land and naval forces, and of directing their operations” (emphasis added). The former power is carried over directly into the Constitution’s list of congressional powers, but the latter is not. This strongly suggests that Congress’s Government-and-Regulation power does not include power to “direct [military] operations.”

From Bruce Bartlett: How Fox News Changed American Media and Political Dynamics

A good walk through changes in the media over the past few decades.

- How Fox News Changed American Media and Political Dynamics.

The creation of Fox News in 1996 was an event of deep, yet unappreciated, political and historical importance. For the first time, there was a news source available virtually everywhere in the United States, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, with a conservative tilt. Finally, conservatives did not have to seek out bits of news favorable to their point of view in liberal publications or in small magazines and newsletters. Like someone dying of thirst in the desert, conservatives drank heavily from the Fox waters. Soon, it became the dominant – and in many cases, virtually the only – major news source for millions of Americans. This has had profound political implications that are only starting to be appreciated. Indeed, it can almost be called self-brainwashing – many conservatives now refuse to even listen to any news or opinion not vetted through Fox, and to believe whatever appears on it as the gospel truth.

When Fox News went on the air in 1996, it advertised itself as “fair and balanced,” which implied that its competitors were neither. At the time, there was unquestionably a liberal bias in the major media; not a huge one, but it was pretty consistent across the three major networks, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times and the rest of the elite media. As Dartmouth communications professor Jim Kuypers put it in a 2002 study, “There is a demonstrable liberal bias to the mainstream press in America.”[1]

Surveys regularly showed that very few reporters were Republicans; the bulk said they were independents, with a large percentage belonging to the Democratic Party.[2] Journalists argued that their professionalism kept bias out of their reporting and that, insofar as there was apparent bias, it was due to the nature of the news itself and the discipline of fact-based reportage. But even if the reporting itself was free of bias, there is no question that the issues that most interested reporters tended to be ones more likely to be liberal in nature than conservative. As the late journalist Michael Kelly once explained, “What journalists choose and how journalists frame inescapably arises out of what journalists believe. And, as a group, journalists believe in liberalism and in electing Democrats.”[3] In any event, the view that the media was generally liberal was widespread among the public.[4]

For more:

- How Information Became Ideological.

- The rise of American authoritarianism.

- “They Don’t Give a Damn about Governing” Conservative Media’s Influence on the Republican Party.

- How Fox News Changed American Media and Political Dynamics.

The creation of Fox News in 1996 was an event of deep, yet unappreciated, political and historical importance. For the first time, there was a news source available virtually everywhere in the United States, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, with a conservative tilt. Finally, conservatives did not have to seek out bits of news favorable to their point of view in liberal publications or in small magazines and newsletters. Like someone dying of thirst in the desert, conservatives drank heavily from the Fox waters. Soon, it became the dominant – and in many cases, virtually the only – major news source for millions of Americans. This has had profound political implications that are only starting to be appreciated. Indeed, it can almost be called self-brainwashing – many conservatives now refuse to even listen to any news or opinion not vetted through Fox, and to believe whatever appears on it as the gospel truth.

When Fox News went on the air in 1996, it advertised itself as “fair and balanced,” which implied that its competitors were neither. At the time, there was unquestionably a liberal bias in the major media; not a huge one, but it was pretty consistent across the three major networks, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times and the rest of the elite media. As Dartmouth communications professor Jim Kuypers put it in a 2002 study, “There is a demonstrable liberal bias to the mainstream press in America.”[1]

Surveys regularly showed that very few reporters were Republicans; the bulk said they were independents, with a large percentage belonging to the Democratic Party.[2] Journalists argued that their professionalism kept bias out of their reporting and that, insofar as there was apparent bias, it was due to the nature of the news itself and the discipline of fact-based reportage. But even if the reporting itself was free of bias, there is no question that the issues that most interested reporters tended to be ones more likely to be liberal in nature than conservative. As the late journalist Michael Kelly once explained, “What journalists choose and how journalists frame inescapably arises out of what journalists believe. And, as a group, journalists believe in liberalism and in electing Democrats.”[3] In any event, the view that the media was generally liberal was widespread among the public.[4]

For more:

- How Information Became Ideological.

- The rise of American authoritarianism.

- “They Don’t Give a Damn about Governing” Conservative Media’s Influence on the Republican Party.

A Brief History of the Development of the Seed Industry – The Shift from Public to Private Seed Systems

A great look at the development of an executive agency along with the clientele it serves.

- Click here for the article.

One hundred fifty years ago the United States did not have a commercial seed industry; today we have the world’s largest. Some view this as real progress, a form of genetic Manifest Destiny. A nation once a ‘debtor’ in plant genetics now supplies the world. In 1854, seeds were sourced in the U.S. by way of a small number of horticultural seed catalogs, farmer (or gardener) exchange, on-farm seed saving, and through the beneficence of the United States government. Specifically, beginning in the 1850s, the U.S. Patent and Trade Office (PTO) and congressional representatives saw to the collection, propagation and distribution of varieties to their constituents throughout the states and territories. The program grew quickly so that, by 1861, the PTO had annual distribution of more than 2.4 million packages of seed (containing five packets of different varieties). The flow of seed reached its highest volume in 1897 (under USDA management) – with more than 1.1 billion packets of seed distributed.

The government’s objectives in funding such a massive movement of seed stemmed from the recognition that feeding an expanding continent would require a diversification of foods. To the early colonies, the introduction of wheat, rye, oats, peas, cabbage and many other vegetable crops was as critical to food security as was the adoption of the corn, beans and squash. Immigrants were encourage to bring seed from the old country, founding fathers such as Thomas Jefferson engaged in seed-exchange societies, and by 1819 the U.S. Treasury Department issued a directive to its overseas consultants and Navy officers to systematically collect plant materials.

The first commercial seed crop was not produced until 1866—cabbage seed produced on Long Island for the U.S. wholesale market. The industry flourished to some degree, but early seed trade professionals felt their growth was stymied by the U.S. government programs as well as the self-replicating nature of their product (that is, the factory contained within that product). In 1883, the American Seed Trade Association (ASTA) formed and immediately lobbied for the cessation of the government programs. The organization developed powerful allies, such as Grover Cleveland’s Secretary of Agriculture, J. Sterling Morton, who wrote that the government giveaway was “antagonistic to seed as a commodity-form and in direct competition with the private seed trade.” But the program was very popular with constituents, and the USDA’s seed budget was kept intact – at one point counting for a full 10 percent of the agency’s overall annual expenditures.

In the early part of the 20th century, the first wave of hybrids began to provide seed companies with a potential increase in product profitability (as farmers would now need to return to the seed distributor for materials each year). However, most of the hybrid development was occurring at Land Grant Universities, and these universities refused to give the companies exclusive rights to the seed. Once again, the industry felt its growth hindered by federal programs and complained of unfair trade practices. Mounting data also indicated a slowing in yield increases from seed developed in government programs. The industry used this last point to strengthen its argument for the privatization of seed development in order to foster greater food security.

In 1924, after more than 40 years of lobbying, ASTA succeeded in convincing Congress to cut the USDA seed distribution programs. The USDA still supported breeding at the state agricultural schools, and for a time these programs continued to compete with seed companies by developing ‘finished’ commercial varieties.

For more:

- Wikipedia: Origins of the Department of Agriculture.

- Wikipedia: Diamond v. Chakrabarty.

- Click here for the article.

One hundred fifty years ago the United States did not have a commercial seed industry; today we have the world’s largest. Some view this as real progress, a form of genetic Manifest Destiny. A nation once a ‘debtor’ in plant genetics now supplies the world. In 1854, seeds were sourced in the U.S. by way of a small number of horticultural seed catalogs, farmer (or gardener) exchange, on-farm seed saving, and through the beneficence of the United States government. Specifically, beginning in the 1850s, the U.S. Patent and Trade Office (PTO) and congressional representatives saw to the collection, propagation and distribution of varieties to their constituents throughout the states and territories. The program grew quickly so that, by 1861, the PTO had annual distribution of more than 2.4 million packages of seed (containing five packets of different varieties). The flow of seed reached its highest volume in 1897 (under USDA management) – with more than 1.1 billion packets of seed distributed.

The government’s objectives in funding such a massive movement of seed stemmed from the recognition that feeding an expanding continent would require a diversification of foods. To the early colonies, the introduction of wheat, rye, oats, peas, cabbage and many other vegetable crops was as critical to food security as was the adoption of the corn, beans and squash. Immigrants were encourage to bring seed from the old country, founding fathers such as Thomas Jefferson engaged in seed-exchange societies, and by 1819 the U.S. Treasury Department issued a directive to its overseas consultants and Navy officers to systematically collect plant materials.

The first commercial seed crop was not produced until 1866—cabbage seed produced on Long Island for the U.S. wholesale market. The industry flourished to some degree, but early seed trade professionals felt their growth was stymied by the U.S. government programs as well as the self-replicating nature of their product (that is, the factory contained within that product). In 1883, the American Seed Trade Association (ASTA) formed and immediately lobbied for the cessation of the government programs. The organization developed powerful allies, such as Grover Cleveland’s Secretary of Agriculture, J. Sterling Morton, who wrote that the government giveaway was “antagonistic to seed as a commodity-form and in direct competition with the private seed trade.” But the program was very popular with constituents, and the USDA’s seed budget was kept intact – at one point counting for a full 10 percent of the agency’s overall annual expenditures.

In the early part of the 20th century, the first wave of hybrids began to provide seed companies with a potential increase in product profitability (as farmers would now need to return to the seed distributor for materials each year). However, most of the hybrid development was occurring at Land Grant Universities, and these universities refused to give the companies exclusive rights to the seed. Once again, the industry felt its growth hindered by federal programs and complained of unfair trade practices. Mounting data also indicated a slowing in yield increases from seed developed in government programs. The industry used this last point to strengthen its argument for the privatization of seed development in order to foster greater food security.

In 1924, after more than 40 years of lobbying, ASTA succeeded in convincing Congress to cut the USDA seed distribution programs. The USDA still supported breeding at the state agricultural schools, and for a time these programs continued to compete with seed companies by developing ‘finished’ commercial varieties.

For more:

- Wikipedia: Origins of the Department of Agriculture.

- Wikipedia: Diamond v. Chakrabarty.

Monday, November 5, 2018

Thursday, November 1, 2018

From Vox: Why Trump can raise steel tariffs without Congress

- Click here for the article.

Why the president can impose tariffs without Congress’s approval

The Constitution is pretty clear: It’s in Congress’s power “to lay and collect taxes, duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States,” and regulate trade between the US and other countries.

But over the past century, Congress has shifted many of the powers to raise and lower tariffs to the executive branch (a concentration of power that conservatives now decry).

There are many ways the president can impose tariffs without congressional approval. To name a few:

- Through the Trading With the Enemy Act of 1917, the president can impose a tariff during a time of war. But the country doesn’t need to be at war with a specific country — just generally somewhere where the tariffs would apply. (This is how Richard Nixonimposed a 10 percent tariff in 1971, citing the Korean War.)

- The Trade Act of 1974 allows the president to implement a 15 percent tariff for 150 days if there is “an adverse impact on national security from imports.” After 150 days, the trade policy would need congressional approval.

- There’s the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, which would allow the president to implement tariffs during a national emergency.

Trump’s White House cited Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, a provision that gives the secretary of commerce the authority to investigate and determine the impacts of any import on the national security of the United States — and the president the power to adjust tariffs accordingly.

In this case, Wilbur Ross, Trump’s commerce secretary, conducted an investigation, which Trump called for last April, into the impacts of steel and aluminum imports. That report was enough legal justification for Trump to bypass both Congress and the independent US International Trade Commission (USITC), which is typically called on to weigh in on proposed tariffs. (When President George W. Bush imposed steel tariffs in 2002 as temporary safeguards, it required USITC oversight.)

Why the president can impose tariffs without Congress’s approval

The Constitution is pretty clear: It’s in Congress’s power “to lay and collect taxes, duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States,” and regulate trade between the US and other countries.

But over the past century, Congress has shifted many of the powers to raise and lower tariffs to the executive branch (a concentration of power that conservatives now decry).

There are many ways the president can impose tariffs without congressional approval. To name a few:

- Through the Trading With the Enemy Act of 1917, the president can impose a tariff during a time of war. But the country doesn’t need to be at war with a specific country — just generally somewhere where the tariffs would apply. (This is how Richard Nixonimposed a 10 percent tariff in 1971, citing the Korean War.)

- The Trade Act of 1974 allows the president to implement a 15 percent tariff for 150 days if there is “an adverse impact on national security from imports.” After 150 days, the trade policy would need congressional approval.

- There’s the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, which would allow the president to implement tariffs during a national emergency.

Trump’s White House cited Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, a provision that gives the secretary of commerce the authority to investigate and determine the impacts of any import on the national security of the United States — and the president the power to adjust tariffs accordingly.

In this case, Wilbur Ross, Trump’s commerce secretary, conducted an investigation, which Trump called for last April, into the impacts of steel and aluminum imports. That report was enough legal justification for Trump to bypass both Congress and the independent US International Trade Commission (USITC), which is typically called on to weigh in on proposed tariffs. (When President George W. Bush imposed steel tariffs in 2002 as temporary safeguards, it required USITC oversight.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)