Newsworthy - also applicable to your chapters on federalism, elections, and the presidency.

- Click here for the article.

Who gets to decide when an election is held?

There are different sets of rules for congressional elections and presidential elections.

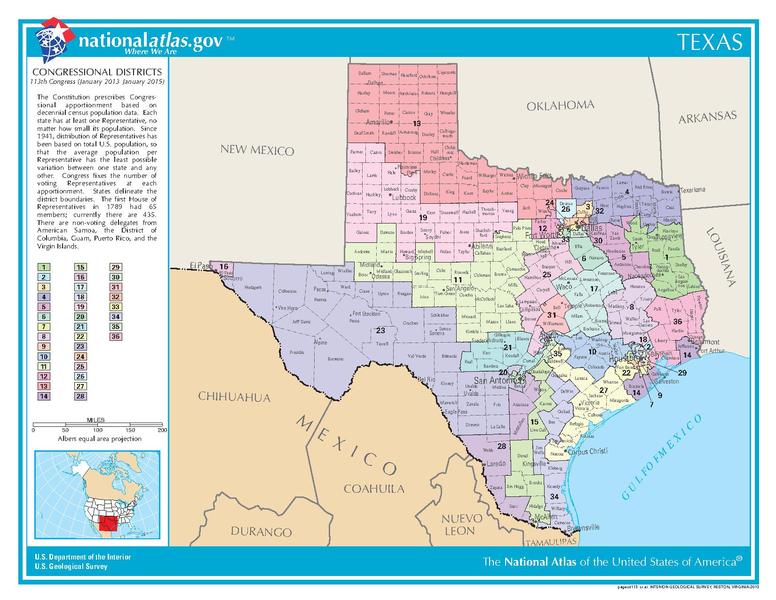

For congressional elections, the Constitution provides that “the times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by law make or alter such regulations, except as to the places of choosing Senators.” This means that both Congress and state lawmakers have control over when a congressional election is held, but Congress has the final word if there’s a disagreement.

Congress has set the date of House and Senate elections for “the Tuesday next after the 1st Monday in November.” Neither Trump nor any state official has the power to alter this date. Only a subsequent act of Congress could do so.

The picture for presidential elections is slightly more complicated. A federal statute does provide that “the electors of President and Vice President shall be appointed, in each State, on the Tuesday next after the first Monday in November,” so states must choose members of the Electoral College on the same day as a congressional election takes place.

That said, there is technically no constitutional requirement that a state must hold an election to choose members of the Electoral College. The Constitution provides that “each state shall appoint, in such manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a number of electors, equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress.” So a state legislature could theoretically decide to select presidential electors out of a hat. More worrisome, a legislature controlled by one party could potentially appoint loyal members of that party directly to the Electoral College.

Yet while state lawmakers theoretically have this power, the idea that presidents are chosen by popular election is now so ingrained into our culture that it is highly unlikely any state legislature would try to appoint electors directly. By 1832, every US state except South Carolina used a popular election to choose members of the Electoral College. South Carolina came around in the 1860s.

Moreover, once a state decides to hold an election to choose members of the Electoral College, all voters must be afforded equal status. As the Supreme Court explained in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections (1966), “once the franchise is granted to the electorate, lines may not be drawn which are inconsistent with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Additionally, even if a state did decide to appoint electors directly, that would require the state to enact a law changing its method of selecting members of the Electoral College. Several crucial swing states, including Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina, have Democratic governors who could veto such legislation.

All of which is a long way of saying that the risk that an election will be outright canceled — or that a state may try to take the power to remove President Trump away from its people — is exceedingly low.

Thursday, July 30, 2020

Wednesday, July 29, 2020

From Wikipedia: Federal law enforcement in the United States

For a good look at the range of agencies that have some type of law enforcement entity:

- Click here for the entry.

- Click here for the entry.

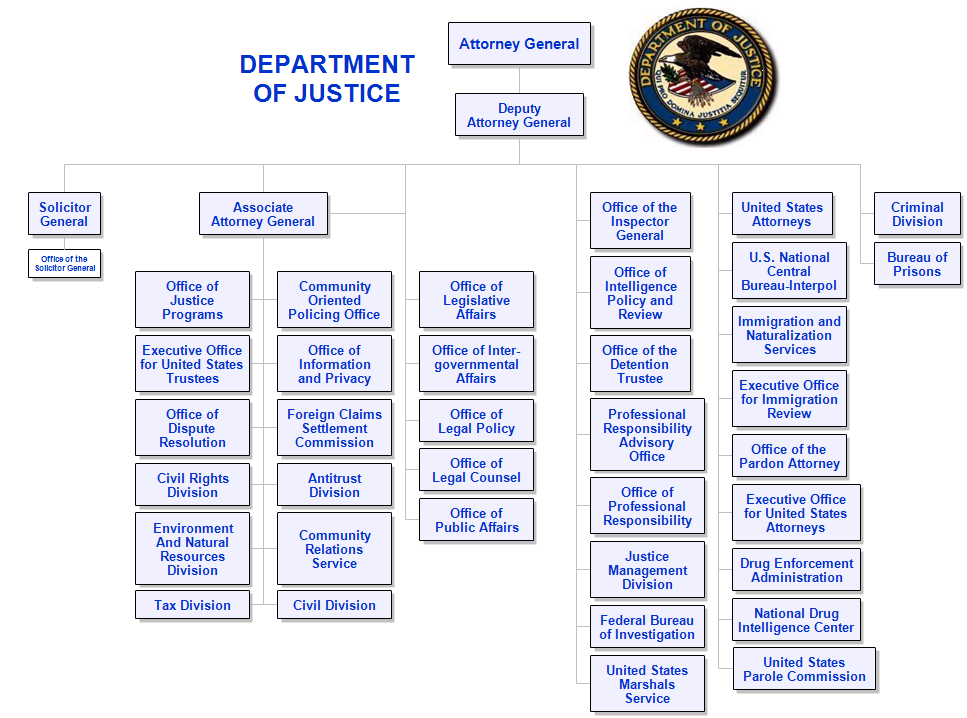

From the House Judiciary Committee: Oversight of the Department of Justice

An example of checks and balances.

- Click here for the page.

For more on the Department of Justice, click on the Wikipedia page.

For more on the Attorney General, click here.

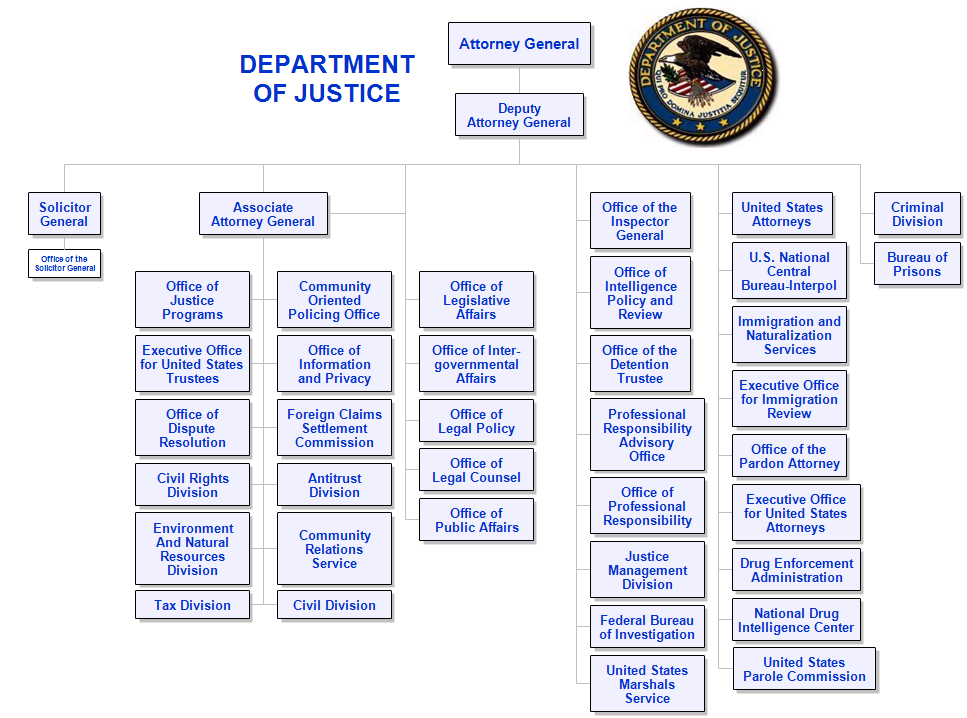

Here is its organizational chart.

- Click here for the page.

For more on the Department of Justice, click on the Wikipedia page.

For more on the Attorney General, click here.

Here is its organizational chart.

From the Cato Institute: The Expanding Federal Police Power

In light of recent events involving federal law enforcement, I thought this would be appropriate for this week's written assignment.

It's important to note that law enforcement is not an enumerated power granted to the national government in the Constitution. It is a power reserved to the states. So the constitutional basis of that power, and the relationship it has with state and local law enforcement is largely undefined.

The article focuses more on the militarization of the police, and the issues related to it. This includes a look at the difference between police forces and the military.

Tell what's going on here.

- Click here for it.

It's important to note that law enforcement is not an enumerated power granted to the national government in the Constitution. It is a power reserved to the states. So the constitutional basis of that power, and the relationship it has with state and local law enforcement is largely undefined.

The article focuses more on the militarization of the police, and the issues related to it. This includes a look at the difference between police forces and the military.

Tell what's going on here.

- Click here for it.

Wednesday, July 22, 2020

From Roll Call: Cheney and Gaetz and Massie and Trump: House GOP tangled up over loyalty

For your next written assignment - tell me what's happening here. How does it illustrate concepts in your textbook - notably the chapters on elections, political parties, and Congress.

What is the House Republican Conference anyway?

- Click here for the article.

Hours after the first in-person House Republican Conference meeting in months erupted in tensions between Chairwoman Liz Cheney and several rank-and-file members, Cheney and other GOP leaders sought to present a united front, even as she stood by the positions that got her crossways with colleagues.

At the Tuesday morning meeting, Cheney was sharply criticized by Florida’s Matt Gaetz and others for not supporting Kentucky’s Thomas Massie in his primary, for not backing President Donald Trump strongly enough, and for showing support for Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, during the coronavirus pandemic that has killed more than 140,000 Americans and counting.

Cheney said she respects Massie and looks forward to working with him and winning the majority come November.

According to a person in the room, the conference meeting started to get messy during its open-mic session. That’s when Massie and Gaetz lined up, with two mics set up in different parts of the room. Cheney called on Gaetz, who said he wanted to let Massie speak first. Cheney said, “That’s not how it works,” which set the stage for more tension.

Massie and Gaetz then called out Cheney for claiming their conference was united when she donated the maximum amount to Massie’s primary opponent, Todd McMurtry. Massie coasted to a win over McMurtry in last month’s primary. Cheney called Massie a “special case,” according to the source in the room.

What is the House Republican Conference anyway?

- Click here for the article.

Hours after the first in-person House Republican Conference meeting in months erupted in tensions between Chairwoman Liz Cheney and several rank-and-file members, Cheney and other GOP leaders sought to present a united front, even as she stood by the positions that got her crossways with colleagues.

At the Tuesday morning meeting, Cheney was sharply criticized by Florida’s Matt Gaetz and others for not supporting Kentucky’s Thomas Massie in his primary, for not backing President Donald Trump strongly enough, and for showing support for Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, during the coronavirus pandemic that has killed more than 140,000 Americans and counting.

Cheney said she respects Massie and looks forward to working with him and winning the majority come November.

According to a person in the room, the conference meeting started to get messy during its open-mic session. That’s when Massie and Gaetz lined up, with two mics set up in different parts of the room. Cheney called on Gaetz, who said he wanted to let Massie speak first. Cheney said, “That’s not how it works,” which set the stage for more tension.

Massie and Gaetz then called out Cheney for claiming their conference was united when she donated the maximum amount to Massie’s primary opponent, Todd McMurtry. Massie coasted to a win over McMurtry in last month’s primary. Cheney called Massie a “special case,” according to the source in the room.

Tuesday, July 21, 2020

From Wikipedia: Federal Election Commission

For background on the agency:

- Click here for the link.

FYI: In my opinion, this agency is misnamed. It does not oversee elections, only the financing related to campaigning. Now you know. ;)

Official Duties

The commission's role is limited to the administration of federal campaign finance laws. It enforces limitations and prohibitions on contributions and expenditures, administers the reporting system for campaign finance disclosure, investigates and prosecutes violations (investigations are typically initiated by complaints from other candidates, parties, watchdog groups, and the public), audits a limited number of campaigns and organizations for compliance, and administers the presidential public funding programs for presidential candidates. Until 2014, the committee was also responsible for regulating the nomination of conventions, and defends the statute in challenges to federal election laws and regulations.

The FEC also publishes reports filed by Senate, House of Representatives and presidential campaigns that list how much each campaign has raised and spent, and a list of all donors over $200, along with each donor's home address, employer and job title. This database also goes back to 1980. Private organizations are legally prohibited from using these data to solicit new individual donors (and the FEC authorizes campaigns to include a limited number of "dummy" names as a measure to prevent this), but may use this information to solicit political action committees. The FEC also maintains an active program of public education, directed primarily to explaining the law to the candidates, their campaigns, political parties and other political committees that it regulates.

- Click here for the link.

FYI: In my opinion, this agency is misnamed. It does not oversee elections, only the financing related to campaigning. Now you know. ;)

Official Duties

The commission's role is limited to the administration of federal campaign finance laws. It enforces limitations and prohibitions on contributions and expenditures, administers the reporting system for campaign finance disclosure, investigates and prosecutes violations (investigations are typically initiated by complaints from other candidates, parties, watchdog groups, and the public), audits a limited number of campaigns and organizations for compliance, and administers the presidential public funding programs for presidential candidates. Until 2014, the committee was also responsible for regulating the nomination of conventions, and defends the statute in challenges to federal election laws and regulations.

The FEC also publishes reports filed by Senate, House of Representatives and presidential campaigns that list how much each campaign has raised and spent, and a list of all donors over $200, along with each donor's home address, employer and job title. This database also goes back to 1980. Private organizations are legally prohibited from using these data to solicit new individual donors (and the FEC authorizes campaigns to include a limited number of "dummy" names as a measure to prevent this), but may use this information to solicit political action committees. The FEC also maintains an active program of public education, directed primarily to explaining the law to the candidates, their campaigns, political parties and other political committees that it regulates.

From Roll Call: FEC set to lose its quorum again

This article combines the executive and legislative branched and campaign spending.

- Click here for the article.

The Federal Election Commission, which just recently regained enough members to conduct such routine official business as meetings, is losing yet another commissioner, sidelining the agency tasked with enforcing election laws in a pivotal presidential election year.

GOP commissioner Caroline Hunter is departing on July 3, according to a resignation letter first reported by Politico. That will leave the agency with three members; a quorum requires four commissioners.

Illinois Rep. Rodney Davis, the top Republican on the House Administration panel, which has jurisdiction over federal election matters, said he was concerned the agency would not have a quorum again before the November elections.

“It just goes to the point we’ve been making for a while that we certainly hope that the administration could get some nominations to get a quorum,” Davis said. “I want to thank Commissioner Hunter for her service. She did a great job; sad to see her go. But at the same time, I’d like to press for more urgency in getting a full commission so that they can operate.”

Relevant terms:

- FEC

- GOP

- House Administration

- quorum

- administration

- outside groups

- voters

- enforcement

- campaign finance laws

- oversight

- Campaign Legal Center

- democracy

- accountability

- appointees

- gridlock

- party lines

- Issue One

- nominate

- confirm

- constitutional responsibilities

- Senate Majority Leader

- Institute for Free Speech

- Click here for the article.

The Federal Election Commission, which just recently regained enough members to conduct such routine official business as meetings, is losing yet another commissioner, sidelining the agency tasked with enforcing election laws in a pivotal presidential election year.

GOP commissioner Caroline Hunter is departing on July 3, according to a resignation letter first reported by Politico. That will leave the agency with three members; a quorum requires four commissioners.

Illinois Rep. Rodney Davis, the top Republican on the House Administration panel, which has jurisdiction over federal election matters, said he was concerned the agency would not have a quorum again before the November elections.

“It just goes to the point we’ve been making for a while that we certainly hope that the administration could get some nominations to get a quorum,” Davis said. “I want to thank Commissioner Hunter for her service. She did a great job; sad to see her go. But at the same time, I’d like to press for more urgency in getting a full commission so that they can operate.”

Relevant terms:

- FEC

- GOP

- House Administration

- quorum

- administration

- outside groups

- voters

- enforcement

- campaign finance laws

- oversight

- Campaign Legal Center

- democracy

- accountability

- appointees

- gridlock

- party lines

- Issue One

- nominate

- confirm

- constitutional responsibilities

- Senate Majority Leader

- Institute for Free Speech

Friday, July 17, 2020

The rules for voting eligibility in Texas are different than those for running for office and serving on a jury

This is the last section of the memo below:

OTHER ISSUES

The requirements for voting and candidacy are often confused. Under Texas law, the rules are different for voting and candidacy. Section 141.001 of the Texas Election Code generally provides that to be eligible to be a candidate for, or elected or appointed to, a public elective office, a person must have not been finally convicted of a felony from which the person has not been pardoned or otherwise released from the resulting disabilities. This means there is no automatic restoration of the right to be a candidate, as there is for voting purposes, after a full discharge. Absent a pardon, the candidate must have obtained a judicial release from his or her disabilities in order to run for any office to which this section applies.

Similarly, the requirements for voting and for serving on a jury are different. Section 62.102 of the Government Code provides that a person who has been finally convicted of a felony is not eligible to serve on a jury, and that right may not be automatically restored as it is for voters.

Candidacy:

Sec. 141.001. ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS FOR PUBLIC OFFICE. (a) To be eligible to be a candidate for, or elected or appointed to, a public elective office in this state, a person must:

(1) be a United States citizen;

(2) be 18 years of age or older on the first day of the term to be filled at the election or on the date of appointment, as applicable;

(3) have not been determined by a final judgment of a court exercising probate jurisdiction to be:

(A) totally mentally incapacitated; or

(B) partially mentally incapacitated without the right to vote;

(4) have not been finally convicted of a felony from which the person has not been pardoned or otherwise released from the resulting disabilities;

Jury Service

Sec. 62.102. GENERAL QUALIFICATIONS FOR JURY SERVICE. A person is disqualified to serve as a petit juror unless the person:

(1) is at least 18 years of age;

(2) is a citizen of the United States;

(3) is a resident of this state and of the county in which the person is to serve as a juror;

(4) is qualified under the constitution and laws to vote in the county in which the person is to serve as a juror;

(5) is of sound mind and good moral character;

(6) is able to read and write;

(7) has not served as a petit juror for six days during the preceding three months in the county court or during the preceding six months in the district court;

(8) has not been convicted of misdemeanor theft or a felony; and

(9) is not under indictment or other legal accusation for misdemeanor theft or a felony.

OTHER ISSUES

The requirements for voting and candidacy are often confused. Under Texas law, the rules are different for voting and candidacy. Section 141.001 of the Texas Election Code generally provides that to be eligible to be a candidate for, or elected or appointed to, a public elective office, a person must have not been finally convicted of a felony from which the person has not been pardoned or otherwise released from the resulting disabilities. This means there is no automatic restoration of the right to be a candidate, as there is for voting purposes, after a full discharge. Absent a pardon, the candidate must have obtained a judicial release from his or her disabilities in order to run for any office to which this section applies.

Similarly, the requirements for voting and for serving on a jury are different. Section 62.102 of the Government Code provides that a person who has been finally convicted of a felony is not eligible to serve on a jury, and that right may not be automatically restored as it is for voters.

Candidacy:

Sec. 141.001. ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS FOR PUBLIC OFFICE. (a) To be eligible to be a candidate for, or elected or appointed to, a public elective office in this state, a person must:

(1) be a United States citizen;

(2) be 18 years of age or older on the first day of the term to be filled at the election or on the date of appointment, as applicable;

(3) have not been determined by a final judgment of a court exercising probate jurisdiction to be:

(A) totally mentally incapacitated; or

(B) partially mentally incapacitated without the right to vote;

(4) have not been finally convicted of a felony from which the person has not been pardoned or otherwise released from the resulting disabilities;

Jury Service

Sec. 62.102. GENERAL QUALIFICATIONS FOR JURY SERVICE. A person is disqualified to serve as a petit juror unless the person:

(1) is at least 18 years of age;

(2) is a citizen of the United States;

(3) is a resident of this state and of the county in which the person is to serve as a juror;

(4) is qualified under the constitution and laws to vote in the county in which the person is to serve as a juror;

(5) is of sound mind and good moral character;

(6) is able to read and write;

(7) has not served as a petit juror for six days during the preceding three months in the county court or during the preceding six months in the district court;

(8) has not been convicted of misdemeanor theft or a felony; and

(9) is not under indictment or other legal accusation for misdemeanor theft or a felony.

From the Texas Secretary of States' Office: Effect of Felony Conviction on Voter Registration

An example of communication between the Texas Secretary of State - who oversees election laws in the state - and voter registrars, who are appointed at the county level. This concerns potential challenges to voter registration based on felony convictions.

TO: Voter Registrars

FROM: Ann McGeehan, Director of Elections

DATE: August 3, 2004

RE: Effect of Felony Conviction on Voter Registration

Due to recent questions posed to this office concerning the effect of a felony conviction on voter registration, we are issuing this memorandum to set out basic rules and guidelines governing this issue.

GENERAL ELIGIBILITY RULES

As you are well aware, a person who is finally convicted of a felony is not eligible to register to vote (what is legally considered a final felony conviction is set forth in more detail under "Final Felony Convictions" below). Pursuant to Section 11.002 of the Texas Election Code (the "Code"), once a felon has successfully completed his or her punishment, including any term of incarceration, parole, supervision, period of probation, or has been pardoned, then that person is immediately eligible to register to vote.

PROCESS FOR CHALLENGING REGISTRATION AND SUGGESTIONS

On a weekly basis, this office receives information from the Department of Public Safety ("DPS") regarding all persons in the state who have been finally convicted of a felony. We match the DPS data against our statewide file of registered voters, and when we find a possible match, we forward that information to the appropriate county for action. This information is forwarded to the counties on a weekly basis via the WEB browser, or for TVRS counties, it is posted in the pending action window. It is our official advice not to immediately cancel a voter whom we have identified as a possible convicted felon. DPS has cautioned us that felons are frequently convicted under false names. When you receive information from this office regarding a possible convicted felon on your voter registration roll, you should investigate the voter registration of that individual pursuant to Section 16.033 of the Code. To investigate a registration, you must send the voter written notice of the investigation and warn the voter that his or her registration may be cancelled if he or she does not respond within 30 days.

NEW APPLICATIONS

We have recently learned that some counties may be retaining the weekly data from the state regarding possible felon information and later challenging voter registration applications of new applicants based on this information. We advise against this. First, this type of challenge is not expressly authorized by the Code. Second, due to the many variables involved in sentencing, it is possible that a finally convicted felon may complete his punishment and be released from all disabilities in a very short amount of time (in some cases, days or months from date of conviction). Accordingly, we advise that you NOT challenge a new application based solely on information from dated weekly reports that you have retained.

FINAL FELONY CONVICTIONS

Please also consider the following information before you challenge an application on the grounds of felony conviction:

- A conviction on appeal is not considered a final felony conviction.

- "Deferred adjudication" is not considered a final felony conviction. Article 42.12, Section 5, Texas Code of Criminal Procedure.

- Mere prosecution, indictment or other criminal procedures leading up to, but not yet resulting in the final conviction, are not final felony convictions.

TO: Voter Registrars

FROM: Ann McGeehan, Director of Elections

DATE: August 3, 2004

RE: Effect of Felony Conviction on Voter Registration

Due to recent questions posed to this office concerning the effect of a felony conviction on voter registration, we are issuing this memorandum to set out basic rules and guidelines governing this issue.

GENERAL ELIGIBILITY RULES

As you are well aware, a person who is finally convicted of a felony is not eligible to register to vote (what is legally considered a final felony conviction is set forth in more detail under "Final Felony Convictions" below). Pursuant to Section 11.002 of the Texas Election Code (the "Code"), once a felon has successfully completed his or her punishment, including any term of incarceration, parole, supervision, period of probation, or has been pardoned, then that person is immediately eligible to register to vote.

PROCESS FOR CHALLENGING REGISTRATION AND SUGGESTIONS

On a weekly basis, this office receives information from the Department of Public Safety ("DPS") regarding all persons in the state who have been finally convicted of a felony. We match the DPS data against our statewide file of registered voters, and when we find a possible match, we forward that information to the appropriate county for action. This information is forwarded to the counties on a weekly basis via the WEB browser, or for TVRS counties, it is posted in the pending action window. It is our official advice not to immediately cancel a voter whom we have identified as a possible convicted felon. DPS has cautioned us that felons are frequently convicted under false names. When you receive information from this office regarding a possible convicted felon on your voter registration roll, you should investigate the voter registration of that individual pursuant to Section 16.033 of the Code. To investigate a registration, you must send the voter written notice of the investigation and warn the voter that his or her registration may be cancelled if he or she does not respond within 30 days.

NEW APPLICATIONS

We have recently learned that some counties may be retaining the weekly data from the state regarding possible felon information and later challenging voter registration applications of new applicants based on this information. We advise against this. First, this type of challenge is not expressly authorized by the Code. Second, due to the many variables involved in sentencing, it is possible that a finally convicted felon may complete his punishment and be released from all disabilities in a very short amount of time (in some cases, days or months from date of conviction). Accordingly, we advise that you NOT challenge a new application based solely on information from dated weekly reports that you have retained.

FINAL FELONY CONVICTIONS

Please also consider the following information before you challenge an application on the grounds of felony conviction:

- A conviction on appeal is not considered a final felony conviction.

- "Deferred adjudication" is not considered a final felony conviction. Article 42.12, Section 5, Texas Code of Criminal Procedure.

- Mere prosecution, indictment or other criminal procedures leading up to, but not yet resulting in the final conviction, are not final felony convictions.

From the Texas State Law Library: Reentry Resources for Ex-Offenders

All you need to know about regaining the right to vote in Texas if you have been convicted of a felony and have served all your time.

- Click here for it.

- Click here for it.

Felon Voting Rights in Texas

The specifics are covered in Article Six of the Texas Constitution.

Remember that the states are in charge of elections.

Here is the text:

Sec. 1. CLASSES OF PERSONS NOT ALLOWED TO VOTE. (a) The following classes of persons shall not be allowed to vote in this State:

(1) persons under 18 years of age;

(2) persons who have been determined mentally incompetent by a court, subject to such exceptions as the Legislature may make; and

(3) persons convicted of any felony, subject to such exceptions as the Legislature may make.

(b) The legislature shall enact laws to exclude from the right of suffrage persons who have been convicted of bribery, perjury, forgery, or other high crimes.

Here are the exceptions the Legislature has made.

From Texas' Elections Code:

Sec. 11.002. QUALIFIED VOTER. (a) In this code, "qualified voter" means a person who:

(1) is 18 years of age or older;

(2) is a United States citizen;

(3) has not been determined by a final judgment of a court exercising probate jurisdiction to be:

(A) totally mentally incapacitated; or

(B) partially mentally incapacitated without the right to vote;

(4) has not been finally convicted of a felony or, if so convicted, has:

(A) fully discharged the person's sentence, including any term of incarceration, parole, or supervision, or completed a period of probation ordered by any court; or

(B) been pardoned or otherwise released from the resulting disability to vote;

(5) is a resident of this state; and

(6) is a registered voter.

(b) For purposes of Subsection (a)(4), a person is not considered to have been finally convicted of an offense for which the criminal proceedings are deferred without an adjudication of guilt.

And wait, there's more:

Sec. 13.001. ELIGIBILITY FOR REGISTRATION. (a) To be eligible for registration as a voter in this state, a person must:

(1) be 18 years of age or older;

(2) be a United States citizen;

(3) not have been determined by a final judgment of a court exercising probate jurisdiction to be:

(A) totally mentally incapacitated; or

(B) partially mentally incapacitated without the right to vote;

(4) not have been finally convicted of a felony or, if so convicted, must have:

(A) fully discharged the person's sentence, including any term of incarceration, parole, or supervision, or completed a period of probation ordered by any court; or

(B) been pardoned or otherwise released from the resulting disability to vote; and

(5) be a resident of the county in which application for registration is made.

(b) To be eligible to apply for registration, a person must, on the date the registration application is submitted to the registrar, be at least 17 years and 10 months of age and satisfy the requirements of Subsection (a) except for age.

(c) For purposes of Subsection (a)(4), a person is not considered to have been finally convicted of an offense for which the criminal proceedings are deferred without an adjudication of guilt.

Remember that the states are in charge of elections.

Here is the text:

Sec. 1. CLASSES OF PERSONS NOT ALLOWED TO VOTE. (a) The following classes of persons shall not be allowed to vote in this State:

(1) persons under 18 years of age;

(2) persons who have been determined mentally incompetent by a court, subject to such exceptions as the Legislature may make; and

(3) persons convicted of any felony, subject to such exceptions as the Legislature may make.

(b) The legislature shall enact laws to exclude from the right of suffrage persons who have been convicted of bribery, perjury, forgery, or other high crimes.

Here are the exceptions the Legislature has made.

From Texas' Elections Code:

Sec. 11.002. QUALIFIED VOTER. (a) In this code, "qualified voter" means a person who:

(1) is 18 years of age or older;

(2) is a United States citizen;

(3) has not been determined by a final judgment of a court exercising probate jurisdiction to be:

(A) totally mentally incapacitated; or

(B) partially mentally incapacitated without the right to vote;

(4) has not been finally convicted of a felony or, if so convicted, has:

(A) fully discharged the person's sentence, including any term of incarceration, parole, or supervision, or completed a period of probation ordered by any court; or

(B) been pardoned or otherwise released from the resulting disability to vote;

(5) is a resident of this state; and

(6) is a registered voter.

(b) For purposes of Subsection (a)(4), a person is not considered to have been finally convicted of an offense for which the criminal proceedings are deferred without an adjudication of guilt.

And wait, there's more:

Sec. 13.001. ELIGIBILITY FOR REGISTRATION. (a) To be eligible for registration as a voter in this state, a person must:

(1) be 18 years of age or older;

(2) be a United States citizen;

(3) not have been determined by a final judgment of a court exercising probate jurisdiction to be:

(A) totally mentally incapacitated; or

(B) partially mentally incapacitated without the right to vote;

(4) not have been finally convicted of a felony or, if so convicted, must have:

(A) fully discharged the person's sentence, including any term of incarceration, parole, or supervision, or completed a period of probation ordered by any court; or

(B) been pardoned or otherwise released from the resulting disability to vote; and

(5) be a resident of the county in which application for registration is made.

(b) To be eligible to apply for registration, a person must, on the date the registration application is submitted to the registrar, be at least 17 years and 10 months of age and satisfy the requirements of Subsection (a) except for age.

(c) For purposes of Subsection (a)(4), a person is not considered to have been finally convicted of an offense for which the criminal proceedings are deferred without an adjudication of guilt.

Felon Voting Rights

A few sources for more info about the variety of laws related to felons in the US.

National Conference of State Legislatures: Felon Voting Rights.

American Civil Liberties Union: Felony Disenfranchisement Laws.

National State Center for Courts: The Future of Restoring Voting Rights for Ex-Felons.

The Sentencing Project: Felony Disenfranchisement.

Note: each of these are interest groups. They're covered in the chapter on Interest Groups and Political Parties. The ACLU is also prominent in the chapters on civil liberties and civil rights.

From pro-con.org.

National Conference of State Legislatures: Felon Voting Rights.

American Civil Liberties Union: Felony Disenfranchisement Laws.

National State Center for Courts: The Future of Restoring Voting Rights for Ex-Felons.

The Sentencing Project: Felony Disenfranchisement.

Note: each of these are interest groups. They're covered in the chapter on Interest Groups and Political Parties. The ACLU is also prominent in the chapters on civil liberties and civil rights.

From pro-con.org.

There is a relationship between the right to travel and the right to vote

I just now learned this!

It's from the Dunn decision below, here's the relevant text:

"[F]reedom to travel throughout the United States has long been recognized as a basic right under the Constitution." United States v. Guest, 383 U. S. 745, 383 U. S. 758 (1966). See Passenger Cases, 7 How. 283, 48 U. S. 492 (1849) (Taney, C.J.); Crandall v. Nevada, 6 Wall. 35, 73 U. S. 43-44 (1868); Paul v. Virginia, 8 Wall. 168, 75 U. S. 180 (1869); Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160 (1941); Kent v. Dulles, 357 U. S. 116, 357 U. S. 126 (1958); Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U. S. 618, 394 U. S. 629-631, 394 U. S. 634 (1969); Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. at 400 U. S. 237 (separate opinion of BRENNAN, WHITE, and MARSHALL, JJ.), 400 U. S. 285-286 (STEWART, J., concurring and dissenting, with whom BURGER, C.J., and BLACKMUN, J., joined). And it is clear that the freedom to travel includes the "freedom to enter and abide in any State in the Union," id. at 400 U. S. 285. Obviously, durational residence laws single out the class of bona fide state and county residents who have recently exercised this constitutionally protected right, and penalize such travelers directly. We considered such a durational residence requirement in Shapiro v. Thompson, supra, where the pertinent statutes imposed a one-year waiting period for interstate migrants as a condition to receiving welfare benefits. Although, in Shapiro, we specifically did not decide whether durational residence requirements could be used to determine voting eligibility,

Page 405 U. S. 339

id. at 394 U. S. 638 n. 21, we concluded that, since the right to travel was a constitutionally protected right,

"any classification which serves to penalize the exercise of that right, unless shown to be necessary to promote a compelling governmental interest, is unconstitutional."

Id. at 394 U. S. 634. This compelling state interest test was also adopted in the separate concurrence of MR. JUSTICE STEWART. Preceded by a long line of cases recognizing the constitutional right to travel, and repeatedly reaffirmed in the face of attempts to disregard it, see Wyman v. Bowens, 397 U. S. 49 (1970), and Wyman v. Lopez, 404 U.S. 1055 (1972), Shapiro and the compelling state interest test it articulates control this case.

Tennessee attempts to distinguish Shapiro by urging that "the vice of the welfare statute in Shapiro . . . was its objective to deter interstate travel." Brief for Appellants 13. In Tennessee's view, the compelling state interest test is appropriate only where there is "some evidence to indicate a deterrence of or infringement on the right to travel. . . ." Ibid. Thus, Tennessee seeks to avoid the clear command of Shapiro by arguing that durational residence requirements for voting neither seek to nor actually do deter such travel. In essence, Tennessee argues that the right to travel is not abridged here in any constitutionally relevant sense.

This view represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the law. [Footnote 8] It is irrelevant whether disenfranchisement or denial of welfare is the more potent deterrent to travel. Shapiro did not rest upon a finding that denial of welfare actually deterred travel. Nor have other "right to travel" cases in this Court always relied on the presence of actual deterrence.

By the way, despite the fact that the right to travel is recognized, it is not actually written in the Constitution.

It's from the Dunn decision below, here's the relevant text:

"[F]reedom to travel throughout the United States has long been recognized as a basic right under the Constitution." United States v. Guest, 383 U. S. 745, 383 U. S. 758 (1966). See Passenger Cases, 7 How. 283, 48 U. S. 492 (1849) (Taney, C.J.); Crandall v. Nevada, 6 Wall. 35, 73 U. S. 43-44 (1868); Paul v. Virginia, 8 Wall. 168, 75 U. S. 180 (1869); Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160 (1941); Kent v. Dulles, 357 U. S. 116, 357 U. S. 126 (1958); Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U. S. 618, 394 U. S. 629-631, 394 U. S. 634 (1969); Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. at 400 U. S. 237 (separate opinion of BRENNAN, WHITE, and MARSHALL, JJ.), 400 U. S. 285-286 (STEWART, J., concurring and dissenting, with whom BURGER, C.J., and BLACKMUN, J., joined). And it is clear that the freedom to travel includes the "freedom to enter and abide in any State in the Union," id. at 400 U. S. 285. Obviously, durational residence laws single out the class of bona fide state and county residents who have recently exercised this constitutionally protected right, and penalize such travelers directly. We considered such a durational residence requirement in Shapiro v. Thompson, supra, where the pertinent statutes imposed a one-year waiting period for interstate migrants as a condition to receiving welfare benefits. Although, in Shapiro, we specifically did not decide whether durational residence requirements could be used to determine voting eligibility,

Page 405 U. S. 339

id. at 394 U. S. 638 n. 21, we concluded that, since the right to travel was a constitutionally protected right,

"any classification which serves to penalize the exercise of that right, unless shown to be necessary to promote a compelling governmental interest, is unconstitutional."

Id. at 394 U. S. 634. This compelling state interest test was also adopted in the separate concurrence of MR. JUSTICE STEWART. Preceded by a long line of cases recognizing the constitutional right to travel, and repeatedly reaffirmed in the face of attempts to disregard it, see Wyman v. Bowens, 397 U. S. 49 (1970), and Wyman v. Lopez, 404 U.S. 1055 (1972), Shapiro and the compelling state interest test it articulates control this case.

Tennessee attempts to distinguish Shapiro by urging that "the vice of the welfare statute in Shapiro . . . was its objective to deter interstate travel." Brief for Appellants 13. In Tennessee's view, the compelling state interest test is appropriate only where there is "some evidence to indicate a deterrence of or infringement on the right to travel. . . ." Ibid. Thus, Tennessee seeks to avoid the clear command of Shapiro by arguing that durational residence requirements for voting neither seek to nor actually do deter such travel. In essence, Tennessee argues that the right to travel is not abridged here in any constitutionally relevant sense.

This view represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the law. [Footnote 8] It is irrelevant whether disenfranchisement or denial of welfare is the more potent deterrent to travel. Shapiro did not rest upon a finding that denial of welfare actually deterred travel. Nor have other "right to travel" cases in this Court always relied on the presence of actual deterrence.

By the way, despite the fact that the right to travel is recognized, it is not actually written in the Constitution.

Purcell v. Gonzalez and Dunn v. Blumstein

Purcell v. Gonzalez was mentioned in the decision below as a case stating that voting is a fundamental political right (though that is not clearly stated anywhere in the Constitution).

The Purcell case cites Dunn v. Blumstein as the source of the precedence.

Here background on both cases, both from Oyez.

- Click here for Purcell v. Gonzalez.

Facts of the case: In 2002, Arizona passed Proposition 200, which required a photo ID for voter registration. The Election Assistance Commission (EAC) notified Arizona’s Secretary of State that Proposition 200 conflicted with the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) regarding the need for photo ID as proof of citizenship for mailed voter registration forms. Shortly thereafter, the plaintiffs — Arizona residents, Indian tribes, and community organizations — filed a restraining order to prevent the state of Arizona from enforcing the new rules for voter registration. The petition for a restraining order was denied by the district court. The plaintiffs appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and argued that it should grant an emergency injunction based on the fact that elections were about to begin. The appellate court granted the injunction to stop the enforcement of Proposition 200.

Question: Did the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit err in granting an emergency injunction regarding Proposition 200 close to election time?

Conclusion: In a per curiam decision, the Court held that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit erred in granting an injunction against the enforcement of Proposition 200. Because the lower court’s decision lacked any information regarding how it came to its conclusion, the Supreme Court could not properly assess this decision, so it ordered that the case be remanded.

Justice John Paul Stevens wrote a concurring opinion in which he agreed because there was no discussion of the rationale for requiring identification for voter registration.

- Click here for Dunn v. Blumstein.

Facts of the case: A Tennessee law required a one-year residence in the state and a three-month residence in the county as a precondition for voting. James Blumstein, a university professor who had recently moved to Tennessee, challenged the law by filing suit against Governor Winfield Dunn and other local officials in federal district court.

Question: Did Tennessee's durational residency requirements violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Conclusion: In a 6-to-1 decision, the Court held that the law was an unconstitutional infringement upon the right to vote and the right to travel. Applying a strict equal protection test, the Court found that the law did not necessarily promote a compelling state interest. Justice Marshall argued in the majority opinion that the durational residency requirements were neither the least restrictive means available to prevent electoral fraud nor an appropriate method of guaranteeing the existence of "knowledgeable voters" within the state.

The Purcell case cites Dunn v. Blumstein as the source of the precedence.

Here background on both cases, both from Oyez.

- Click here for Purcell v. Gonzalez.

Facts of the case: In 2002, Arizona passed Proposition 200, which required a photo ID for voter registration. The Election Assistance Commission (EAC) notified Arizona’s Secretary of State that Proposition 200 conflicted with the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) regarding the need for photo ID as proof of citizenship for mailed voter registration forms. Shortly thereafter, the plaintiffs — Arizona residents, Indian tribes, and community organizations — filed a restraining order to prevent the state of Arizona from enforcing the new rules for voter registration. The petition for a restraining order was denied by the district court. The plaintiffs appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and argued that it should grant an emergency injunction based on the fact that elections were about to begin. The appellate court granted the injunction to stop the enforcement of Proposition 200.

Question: Did the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit err in granting an emergency injunction regarding Proposition 200 close to election time?

Conclusion: In a per curiam decision, the Court held that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit erred in granting an injunction against the enforcement of Proposition 200. Because the lower court’s decision lacked any information regarding how it came to its conclusion, the Supreme Court could not properly assess this decision, so it ordered that the case be remanded.

Justice John Paul Stevens wrote a concurring opinion in which he agreed because there was no discussion of the rationale for requiring identification for voter registration.

- Click here for Dunn v. Blumstein.

Facts of the case: A Tennessee law required a one-year residence in the state and a three-month residence in the county as a precondition for voting. James Blumstein, a university professor who had recently moved to Tennessee, challenged the law by filing suit against Governor Winfield Dunn and other local officials in federal district court.

Question: Did Tennessee's durational residency requirements violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Conclusion: In a 6-to-1 decision, the Court held that the law was an unconstitutional infringement upon the right to vote and the right to travel. Applying a strict equal protection test, the Court found that the law did not necessarily promote a compelling state interest. Justice Marshall argued in the majority opinion that the durational residency requirements were neither the least restrictive means available to prevent electoral fraud nor an appropriate method of guaranteeing the existence of "knowledgeable voters" within the state.

BONNIE RAYSOR, ET AL. v. RON DESANTIS, GOVERNOR OF FLORIDA, ET AL

- Click here for the court's ruling stating that they declined to review the case.

Your chapter on the Judiciary discussed the rule of four - look it up. Three justices dissented in the decision. They explained why.

Their decision uses a great deal of terminology central to this class. It's worth a quick read. I'll post some quotes from the text shortly, but here are terms that stick out to me. It also touches on issues central to this week's readings - also next week's.

Since you've taken the first test, many of these should be familiar to you. I hope so anyway, lol.

- voter registration

- federal district court

- circuit court

- judicial federalism

- fundamental political right to vote.

Your chapter on the Judiciary discussed the rule of four - look it up. Three justices dissented in the decision. They explained why.

Their decision uses a great deal of terminology central to this class. It's worth a quick read. I'll post some quotes from the text shortly, but here are terms that stick out to me. It also touches on issues central to this week's readings - also next week's.

Since you've taken the first test, many of these should be familiar to you. I hope so anyway, lol.

- voter registration

- federal district court

- circuit court

- judicial federalism

- fundamental political right to vote.

- amendment

- legislature

- high court

- primary

- Equal Protection Clause

- Due Process Clause

- 24th Amendment

- plaintiffs

- wealth discrimination

- rational basis review

- indigence

- disenfranchisement

- dissent

- legislature

- high court

- primary

- Equal Protection Clause

- Due Process Clause

- 24th Amendment

- plaintiffs

- wealth discrimination

- rational basis review

- indigence

- disenfranchisement

- dissent

From Scotusblog: Justices decline to intervene in Florida voting dispute

Here is an illustration of state control of suffrage.

Recall that the Constitution originally gave this to the fully to the states, and only began placing limits on the states in the 15th Amendment. Aside from what is specifically mentioned in the 15, 19, 24, and 16 Amendments, states can place limits on voting. The two used in Texas are mental incompetence, and felony convictions. In Texas a convicted felon can gain back the right to vote after the sentence has been served, including parole. Each state can set whatever rules it wishes.

Florida does not allow felons to gain the right to vote back at all. That is the issue in this case.

Notice that this is about the ability to pay court costs, fees, and fines, which raises poll tax issues. The Supreme Court, by a 6-3 vote, didn't see a constitutional problem with that.

A secondary issue was wealth discrimination.

- Click here for the story.

The Supreme Court on Thursday rejected a request by Florida voters and civil rights groups to reinstate a ruling that would have cleared the way for thousands of Florida residents who have been convicted of a felony to vote in the state’s upcoming elections. Justice Sonia Sotomayor dissented from the ruling, writing an opinion that was joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Elena Kagan.

At the heart of the dispute is a 2018 amendment to Florida’s constitution that permits people with prior felony convictions to vote once they complete “all terms of their sentence including parole or probation.” In 2019, the state’s legislature passed a law that required residents who have been convicted of a felony to pay all court costs, fees and fines before they can become eligible to vote. Voters challenged the 2019 law, setting off a series of proceedings that culminated in Thursday’s order by the Supreme Court.

A federal district court in Florida initially blocked the state from enforcing the 2019 law on the ground that it discriminates on the basis of wealth. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit upheld that ruling in February. In May, after a full trial, the district court issued a new ruling holding that the law violates the U.S. Constitution’s 24th Amendment, which bars poll taxes. The district court also concluded that because it could take years for the state to figure out how much residents with past convictions must pay to be eligible to vote, the law will discourage voters from registering at all, because they will be afraid that they will be charged with fraud if they make a mistake.

Recall that the Constitution originally gave this to the fully to the states, and only began placing limits on the states in the 15th Amendment. Aside from what is specifically mentioned in the 15, 19, 24, and 16 Amendments, states can place limits on voting. The two used in Texas are mental incompetence, and felony convictions. In Texas a convicted felon can gain back the right to vote after the sentence has been served, including parole. Each state can set whatever rules it wishes.

Florida does not allow felons to gain the right to vote back at all. That is the issue in this case.

Notice that this is about the ability to pay court costs, fees, and fines, which raises poll tax issues. The Supreme Court, by a 6-3 vote, didn't see a constitutional problem with that.

A secondary issue was wealth discrimination.

- Click here for the story.

The Supreme Court on Thursday rejected a request by Florida voters and civil rights groups to reinstate a ruling that would have cleared the way for thousands of Florida residents who have been convicted of a felony to vote in the state’s upcoming elections. Justice Sonia Sotomayor dissented from the ruling, writing an opinion that was joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Elena Kagan.

At the heart of the dispute is a 2018 amendment to Florida’s constitution that permits people with prior felony convictions to vote once they complete “all terms of their sentence including parole or probation.” In 2019, the state’s legislature passed a law that required residents who have been convicted of a felony to pay all court costs, fees and fines before they can become eligible to vote. Voters challenged the 2019 law, setting off a series of proceedings that culminated in Thursday’s order by the Supreme Court.

A federal district court in Florida initially blocked the state from enforcing the 2019 law on the ground that it discriminates on the basis of wealth. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit upheld that ruling in February. In May, after a full trial, the district court issued a new ruling holding that the law violates the U.S. Constitution’s 24th Amendment, which bars poll taxes. The district court also concluded that because it could take years for the state to figure out how much residents with past convictions must pay to be eligible to vote, the law will discourage voters from registering at all, because they will be afraid that they will be charged with fraud if they make a mistake.

Tuesday, July 14, 2020

From Wikipedia: White Primaries

Up until 1944, it was lawful for states to allow racial segregation in primary elections.

Texas was - until recently - a one party state. No Republican party existed until the early 1960s, so the only competition was in the Democratic primary election. The state allowed the party to exclude Black voters, which effectively disenfranchised them.

- Click here for the entry.

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South Carolina (1896), Florida (1902), Mississippi and Alabama (also 1902), Texas (1905), Louisiana and Arkansas (1906), and Georgia (1908). The white primary was one method used by white Democrats to disenfranchise most black and other minority voters. They also passed laws and constitutions with provisions to raise barriers to voter registration, completing disenfranchisement from 1890 to 1908 in all states of the former Confederacy.

The Texas Legislature passed a law in 1923 that allowed political parties to make their own rules for their primaries. The dominant Democratic Party banned black and hispanic minorities from participating. The Supreme Court, in 1927, 1932, and 1935, heard three Texas cases related to white primaries. In the 1927 and 1932 cases, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the plaintiff, saying that state laws establishing a white primary violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Later in 1927 Texas changed its law in response, delegating authority to political parties to establish their own rules for primaries. In Grovey v. Townsend (1935), the Supreme Court ruled that this practice was constitutional, as it was administered by the Democratic Party, which was a private, not a state institution.

In 1944, the Supreme Court ruled 8–1 against the Texas white primary system in Smith v. Allwright. In that case, the Court ruled that the 1923 Texas state law was unconstitutional, because it allowed the state Democratic Party to racially discriminate. After the case, most Southern states ended their selectively inclusive white primaries. They retained other devices of disenfranchisement, particularly in terms of barriers to voter registration, such as poll taxes and literacy tests. These generally survived legal challenges as they applied to all potential voters, but in practice they were administered in a discriminatory manner by white officials. Although the proportion of Southern blacks registered to vote steadily increased from less than 3 percent in 1940 to 29 percent in 1960 and over 40 percent in 1964, gains were minimal in Mississippi, Alabama, North Louisiana and southern parts of Georgia before the Voting Rights Act.

Texas was - until recently - a one party state. No Republican party existed until the early 1960s, so the only competition was in the Democratic primary election. The state allowed the party to exclude Black voters, which effectively disenfranchised them.

- Click here for the entry.

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South Carolina (1896), Florida (1902), Mississippi and Alabama (also 1902), Texas (1905), Louisiana and Arkansas (1906), and Georgia (1908). The white primary was one method used by white Democrats to disenfranchise most black and other minority voters. They also passed laws and constitutions with provisions to raise barriers to voter registration, completing disenfranchisement from 1890 to 1908 in all states of the former Confederacy.

The Texas Legislature passed a law in 1923 that allowed political parties to make their own rules for their primaries. The dominant Democratic Party banned black and hispanic minorities from participating. The Supreme Court, in 1927, 1932, and 1935, heard three Texas cases related to white primaries. In the 1927 and 1932 cases, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the plaintiff, saying that state laws establishing a white primary violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Later in 1927 Texas changed its law in response, delegating authority to political parties to establish their own rules for primaries. In Grovey v. Townsend (1935), the Supreme Court ruled that this practice was constitutional, as it was administered by the Democratic Party, which was a private, not a state institution.

In 1944, the Supreme Court ruled 8–1 against the Texas white primary system in Smith v. Allwright. In that case, the Court ruled that the 1923 Texas state law was unconstitutional, because it allowed the state Democratic Party to racially discriminate. After the case, most Southern states ended their selectively inclusive white primaries. They retained other devices of disenfranchisement, particularly in terms of barriers to voter registration, such as poll taxes and literacy tests. These generally survived legal challenges as they applied to all potential voters, but in practice they were administered in a discriminatory manner by white officials. Although the proportion of Southern blacks registered to vote steadily increased from less than 3 percent in 1940 to 29 percent in 1960 and over 40 percent in 1964, gains were minimal in Mississippi, Alabama, North Louisiana and southern parts of Georgia before the Voting Rights Act.

7/14/20 - Election Day in Texas - Part Three

The national government does not oversee elections in the states. Following the ratification of several amendments (14, 15, 19, 24, 26) as well as the passage of the Voting Rights Act, the national government has provided a degree of protection for the right to vote, but that does not mean that they oversee their operations. They respond if someone claims that their voting rights have been unlawfully impeded.

Elections are overseen, separately, in each of the states in that state's office of the Secretary of State.

- Click here for the Texas Secretary of State (it is part of Texas' plural executive)

Among their duties is establishing the elections calendar in the state.

- Click here for the November 3, 2020 Election Law Calendar.

Elections are overseen, separately, in each of the states in that state's office of the Secretary of State.

- Click here for the Texas Secretary of State (it is part of Texas' plural executive)

Among their duties is establishing the elections calendar in the state.

- Click here for the November 3, 2020 Election Law Calendar.

7/14/20 - Election Day in Texas - Part Two

If you've read the U.S. Constitution clearly - or at all - you'll notice that the national government does not run elections - it gives that responsibility to the states. The U.S. Constitution does establish elected positions, which states are responsible for filling.

Here are the relevant parts of the U.S. Constitution. Notice the repeated mention of states.

Article One:

Section Two:

1. The House of Representatives shall be composed of members chosen every second year by the people of the several States, and the elector in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State Legislature.

3. Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective numbers . . . The actual enumeration shall be made within three years after the first meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent term of ten years, in such manner as they shall by law direct.

4. When vacancies happen in the representation from any State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue writs of election to fill such vacancies.

Section Three:

1. The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, (chosen by the Legislature thereof,) (The preceding five words were superseded by Amendment XVII) for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote.

2. Immediately after they shall be assembled in consequence of the first election, they shall be divided as equally as may be into three classes. The seats of the Senators of the first class shall be vacated at the expiration of the second year, of the second class at the expiration of the fourth year, and of the third class at the expiration of the sixth year, so that one-third may be chosen every second year; and if vacancies happen by resignation, or otherwise, during the recess of the Legislature of any State, the Executive thereof may make temporary appointments until the next meeting of the Legislature, which shall then fill such vacancies.

Section Four:

1. The times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by law make or alter such regulations, except as to the places of choosing Senators.

Article Two:

2. Each State shall appoint, in such manner as the Legislature may direct, a number of electors, equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or person holding an office of trust or profit under the United States, shall be appointed an elector.

- See also the 12th Amendment.

In case you'd like to know where, in Texas, those laws exist, you can look here:

- Texas Election Code.

Here are the relevant parts of the U.S. Constitution. Notice the repeated mention of states.

Article One:

Section Two:

1. The House of Representatives shall be composed of members chosen every second year by the people of the several States, and the elector in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State Legislature.

3. Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective numbers . . . The actual enumeration shall be made within three years after the first meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent term of ten years, in such manner as they shall by law direct.

4. When vacancies happen in the representation from any State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue writs of election to fill such vacancies.

Section Three:

1. The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, (chosen by the Legislature thereof,) (The preceding five words were superseded by Amendment XVII) for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote.

2. Immediately after they shall be assembled in consequence of the first election, they shall be divided as equally as may be into three classes. The seats of the Senators of the first class shall be vacated at the expiration of the second year, of the second class at the expiration of the fourth year, and of the third class at the expiration of the sixth year, so that one-third may be chosen every second year; and if vacancies happen by resignation, or otherwise, during the recess of the Legislature of any State, the Executive thereof may make temporary appointments until the next meeting of the Legislature, which shall then fill such vacancies.

Section Four:

1. The times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by law make or alter such regulations, except as to the places of choosing Senators.

Article Two:

2. Each State shall appoint, in such manner as the Legislature may direct, a number of electors, equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or person holding an office of trust or profit under the United States, shall be appointed an elector.

- See also the 12th Amendment.

In case you'd like to know where, in Texas, those laws exist, you can look here:

- Texas Election Code.

7/14/20 - Election Day in Texas - Part One

As you will notice, we have lots of elections in Texas and across the United States.

What's happening today is the runoff for the party primaries. The purpose of to finalize who will represent each party in the November general elections. Republicans vote in the Republican Primary, Democrats vote in the Democratic Primary.

Each party in Texas uses primary elections to determine their candidates for public office. These were held earlier in the year, but Texas requires a majority vote to win. That means the winner has over 50% of the vote. If no candidate gets a majority, the top two candidates face each other in a runoff.

Again, that's what's happening today.

Actually, it has been happening the previous two weeks since Texas allows for early voting.

For more:

- 6 things to watch in Texas’ primary runoff election.

What's happening today is the runoff for the party primaries. The purpose of to finalize who will represent each party in the November general elections. Republicans vote in the Republican Primary, Democrats vote in the Democratic Primary.

Each party in Texas uses primary elections to determine their candidates for public office. These were held earlier in the year, but Texas requires a majority vote to win. That means the winner has over 50% of the vote. If no candidate gets a majority, the top two candidates face each other in a runoff.

Again, that's what's happening today.

Actually, it has been happening the previous two weeks since Texas allows for early voting.

For more:

- 6 things to watch in Texas’ primary runoff election.

Sunday, July 12, 2020

For Summer 2's Second Written Assignment

From the Texas Tribune:

- Three Texas House runoffs give warring GOP factions chance to settle up before November.

This article is focused on races for the Texas House of Representatives, but it illustrates terms and concepts you will see in the chapters on elections, parties and interest groups.

I want you to read this and explain what it is telling us about competition within the Republican Party, not between Republicans and Democrats.

Relevant terms:

- incumbent

- primary

- hardline conservative

- runoff

- intraparty factions

- grassroots

- Republicans

- political elite

- Texas Right to Life

- Empower Texans

- special interest groups

- Associated Republicans of Texas

- Super PACs

- liberal

- Planned Parenthodd

- Second Amendment

- property tax

- Three Texas House runoffs give warring GOP factions chance to settle up before November.

This article is focused on races for the Texas House of Representatives, but it illustrates terms and concepts you will see in the chapters on elections, parties and interest groups.

I want you to read this and explain what it is telling us about competition within the Republican Party, not between Republicans and Democrats.

Relevant terms:

- incumbent

- primary

- hardline conservative

- runoff

- intraparty factions

- grassroots

- Republicans

- political elite

- Texas Right to Life

- Empower Texans

- special interest groups

- Associated Republicans of Texas

- Super PACs

- liberal

- Planned Parenthodd

- Second Amendment

- property tax

Trump v. Mazars USA, LLP

The second case decided last week concerning the president's immunity from investigations, this time from Congress.

- Click here for the opinion.

For detail:

- ScotusBlog.

- Wikipedia.

Summary from Oyez:

- Click here for it.

Facts of the case: The U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform issued a subpoena to Mazars USA, the accounting firm for Donald Trump (in his capacity as a private citizen) and several of his businesses, demanding private financial records belonging to Trump. According to the Committee, the requested documents would inform its investigation into whether Congress should amend or supplement its ethics-in-government laws. Trump argued that the information serves no legitimate legislative purpose and sued to prevent Mazars from complying with the subpoena.

The district court granted summary judgment for the Committee, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit affirmed, finding the Committee possesses the authority under both the House Rules and the Constitution.

In the consolidated case, Trump v. Deutsche Bank AG, No. 19-760, two committees of the U.S. House of Representatives—the Committee on Financial Services and the Intelligence Committee—issued a subpoena to the creditors of President Trump and several of his businesses. The district court denied Trump’s motion for a preliminary injunction to prevent compliance with the subpoenas, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed in substantial part and remanded in part.

Question: Does the Constitution prohibit subpoenas issued to Donald Trump’s accounting firm requiring it to provide non-privileged financial records relating to Trump (as a private citizen) and some of his businesses?

Conclusion: The courts below did not take adequate account of the significant separation of powers concerns implicated by congressional subpoenas for the President’s information. Chief Justice John Roberts authored the 7-2 majority opinion of the Court.

The Court first acknowledged that this dispute between Congress and the Executive is the first of its kind to reach the Court and that the Court does not take lightly its responsibility to resolve the issue in a manner that ensures “it does not needlessly disturb ‘the compromises and working arrangements’ reached by those branches. Each house of Congress has “indispensable” power “to secure needed information” in order to legislate, including the power to issue a congressional subpoena, provided that the subpoena is “related to, and in furtherance of, a legitimate task of the Congress.” However, the issuance of a congressional subpoena upon the sitting President raises important separation-of-powers concerns. The standard advocated by the President—a “demonstrated, specific need”—is too stringent. At the same time, the standard advocated by the House—a “valid legislative purpose”—does not adequately safeguard the President from an overzealous and perhaps politically motivated Congress.

- Click here for the opinion.

For detail:

- ScotusBlog.

- Wikipedia.

Summary from Oyez:

- Click here for it.

Facts of the case: The U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform issued a subpoena to Mazars USA, the accounting firm for Donald Trump (in his capacity as a private citizen) and several of his businesses, demanding private financial records belonging to Trump. According to the Committee, the requested documents would inform its investigation into whether Congress should amend or supplement its ethics-in-government laws. Trump argued that the information serves no legitimate legislative purpose and sued to prevent Mazars from complying with the subpoena.

The district court granted summary judgment for the Committee, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit affirmed, finding the Committee possesses the authority under both the House Rules and the Constitution.

In the consolidated case, Trump v. Deutsche Bank AG, No. 19-760, two committees of the U.S. House of Representatives—the Committee on Financial Services and the Intelligence Committee—issued a subpoena to the creditors of President Trump and several of his businesses. The district court denied Trump’s motion for a preliminary injunction to prevent compliance with the subpoenas, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed in substantial part and remanded in part.

Question: Does the Constitution prohibit subpoenas issued to Donald Trump’s accounting firm requiring it to provide non-privileged financial records relating to Trump (as a private citizen) and some of his businesses?

Conclusion: The courts below did not take adequate account of the significant separation of powers concerns implicated by congressional subpoenas for the President’s information. Chief Justice John Roberts authored the 7-2 majority opinion of the Court.

The Court first acknowledged that this dispute between Congress and the Executive is the first of its kind to reach the Court and that the Court does not take lightly its responsibility to resolve the issue in a manner that ensures “it does not needlessly disturb ‘the compromises and working arrangements’ reached by those branches. Each house of Congress has “indispensable” power “to secure needed information” in order to legislate, including the power to issue a congressional subpoena, provided that the subpoena is “related to, and in furtherance of, a legitimate task of the Congress.” However, the issuance of a congressional subpoena upon the sitting President raises important separation-of-powers concerns. The standard advocated by the President—a “demonstrated, specific need”—is too stringent. At the same time, the standard advocated by the House—a “valid legislative purpose”—does not adequately safeguard the President from an overzealous and perhaps politically motivated Congress.

What is a grand jury?

The lawsuit in Trump v Vance was over the constitutionality of a state grand jury request for records from President Trump's accountants.

So with that in mind, what exactly is a grand jury and how do they work?

- Wikipedia: Grand juries in the United States.

Grand juries in the United States are groups of citizens empowered by United States federal or state law to conduct legal proceedings, chiefly investigating potential criminal conduct and determining whether criminal charges should be brought. The grand jury originated under the law of England and spread through colonization to other jurisdictions as part of the common law.

. . . Generally speaking, a grand jury may issue an indictment for a crime, also known as a "true bill," only if it finds, based upon the evidence that has been presented to it, that there is probable cause to believe that a crime has been committed by a criminal suspect. Unlike a petit jury, which resolves a particular civil or criminal case, a grand jury (typically having twelve to twenty-three members) serves as a group for a sustained period of time in all or many of the cases that come up in the jurisdiction, generally under the supervision of a federal U.S. attorney, a county district attorney, or a state attorney-general, and hears evidence ex parte (i.e. without suspect or person of interest involvement in the proceedings).