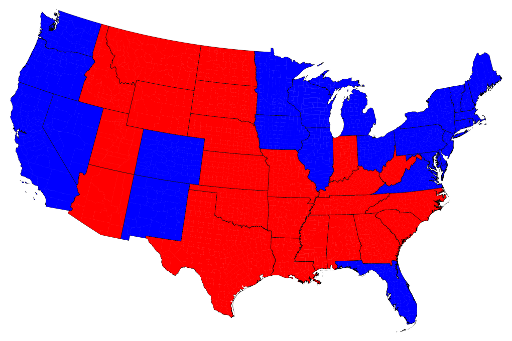

Texas is still Texas, but Rhode Island is now Wyoming and Alaska is California.

A federal lawsuit filed last week in Louisiana contains some of the most startling allegations you will ever see against public school officials accused of unlawfully turning their school into a bastion of Christian belief. In western Louisiana's Sabine Parish, one family alleges, teachers preach Creationism and mock the theory of evolution, routinely lead their students in Christian prayer, give extra credit for Christian responses to assignments, and actively question or deride the religious beliefs of non-Christian students and parents.

Here's the fancy chart:

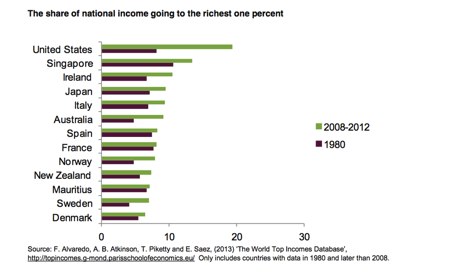

There are a number of key arguments in Piketty’s book. One is that the six-decade period of growing equality in western nations – starting roughly with the onset of World War I and extending into the early 1970s – was unique and highly unlikely to be repeated. That period, Piketty suggests, represented an exception to the more deeply rooted pattern of growing inequality.

According to Piketty, those halcyon six decades were the result of two world wars and the Great Depression. The owners of capital – those at the top of the pyramid of wealth and income – absorbed a series of devastating blows. These included the loss of credibility and authority as markets crashed; physical destruction of capital throughout Europe in both World War I and World War II; the raising of tax rates, especially on high incomes, to finance the wars; high rates of inflation that eroded the assets of creditors; the nationalization of major industries in both England and France; and the appropriation of industries and property in post-colonial countries.

At the same time, the Great Depression produced the New Deal coalition in the United States, which empowered an insurgent labor movement. The postwar period saw huge gains in growth and productivity, the benefits of which were shared with workers who had strong backing from the trade union movement and from the dominant Democratic Party. Widespread support for liberal social and economic policy was so strong that even a Republican president who won easily twice, Dwight D. Eisenhower, recognized that an assault on the New Deal would be futile. In Eisenhower’s words, “Should any political party attempt to abolish Social Security, unemployment insurance, and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear from that party again in our political history.”

The six decades between 1914 and 1973 stand out from the past and future, according to Piketty, because the rate of economic growth exceeded the after-tax rate of return on capital. Since then, the rate of growth of the economy has declined, while the return on capital is rising to its pre-World War I levels.

8:42 p.m.: Support legalization of marijuana?

Dewhurst: Would not legalize marijuana. Get people who have addictions well and not addicted.

Staples: Would not legalize recreational use. We need to be smart on enforcing laws. Need to make sure we have programs in place to deal with perpetual violators of our law. Do not need to lower our standards or allow what is happening elsewhere in the country to happen in Texas. We support local law enforcement and as lieutenant governor I would uphold the laws of the land.

Patrick: A nonstarter for me. I couldn’t believe the president of the U.S. would interject in the parenting of our children to say it’s OK to use marijuana.

Patterson: Federal government should not be involved in criminal justice. It is a state issue. I do agree with Gov. Perry – it is Texas’ decision to make. Do not support legalizing recreational use. Medicinal uses, we should consider that. We should not go back to the ’60s where if one kid had a joint it’s a felony. … FDA would administer it. We have medical barbiturates. We have medical codeine.

“The purpose of my proposal is to eliminate ‘dark money’ from Texas elections by dragging it into the sunlight,” Bresnen wrote to acting Executive Director Natalia Luna Ashley. “Secret money influencing elections — the life blood of self governance — is intolerable as a matter of law and is against the public interest. The Commission should exercise its authority to do something about it.”

The issue of dark money has been a political lightning rod since the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Citizens United vs. the Federal Election Commission. That decision paved a path for outside groups like super PACs and 501(c)(4)s to raise and spend unlimited sums from corporations, labor groups and deep- pocketed individual donors.

And while both 501(c)(4)s and super PACs can accept unlimited sums of cash, only super PACs are required to identify donors.

As a result, super PACs regularly set up sister outfits in the form of a 501(c)(4)s to funnel money anonymously to candidates or to fund attack ads. That’s how they got the ominous title “dark money” groups.

In Texas, the issue hit home during the legislative session when Gov. Rick Perry vetoed a dark money disclosure bill that would have required politically active 501(c)4s to reveal contributors who give more than $1,000 to any dark money group that spends $25,000 or more on politicking.

That measure, sponsored by Sen. Kel Seliger and Rep. Charlie Geren, R-Fort Worth, was intended to require non-profit groups like Empower Texans to report some of its secret donors.

Bresnen’s petition from Tuesday takes aim again at Empower Texans and its president, Michael Quinn Sullivan, saying the “$372,000 in secret political money that Mike Sullivan used in the 2012 elections” was part of the reason he’s asking the commission to step in.

To coordinate education and outreach efforts associated with the Affordable Care Act, the Houston Department of Health and Human Services is taking an approach that mirrors how the Federal Emergency Management Agency might react to a catastrophe.

The Enroll Gulf Coast initiative has set up an “incident command structure” to synchronize the activities of 13 organizations in Harris and 12 nearby counties. An “intelligence committee” created heat maps showing the ZIP codes with the region’s highest number of uninsured residents and “access” points, like community centers and libraries, to connect with people in those neighborhoods. Meanwhile, an “operations committee” uses that information to host canvassing and health insurance enrollment events in targeted neighborhoods. The groups also share an online dashboard to input data and track their coordinated enrollment efforts in real time.

“The number of uninsured people that we have here in Harris County, 1.1 million, yeah, that’s a public health emergency,” said Ben Hernandez, deputy assistant director for the Houston Department of Health and Human Services. “That’s why it’s easy for us to say, 'Let’s treat it like we’d treat a hurricane.'"

While no one believed carrying out the Affordable Care Act in Texas would be easy, a series of additional obstacles has impeded efforts to help the 6.2 million uninsured Texans find health coverage. The launch of the federal marketplace, healthcare.gov, was a technical disaster. The state’s Republican leadership, saying Medicaid is broken, has refused to expand the program for impoverished adults. And last week, the Texas Department of Insurance issued state regulations that added further training and other requirements for the navigators hired and trained by recipients of federal grants to help people enroll in the health marketplace.

Still, government officials and community-based organizations are working together to incorporate new rules, maximize their resources and educate uninsured Texans on how to take advantage of the federal law.

The federal Department of Health and Human Services awarded $11 million to organizations in Texas to hire and train navigators. They are required to receive 20 to 30 hours of training under federal law.

The United Way of Tarrant County received the largest grant, $5.8 million, and has distributed the money to 17 organizations around the state. There are 165 navigators in that consortium, including 13 hired by the city of Houston. To expand its efforts, Hernandez said the Houston health department has trained 90 city employees to become navigators and expanded their job responsibilities.

The Houston health department is also working with government entities and community-based organizations in Dallas, El Paso, Austin and the Rio Grande Valley to extend Enroll Gulf Coast’s strategy across the state, Hernandez said.

Tim McKinney, the chief executive of United Way of Tarrant County, said navigators within their consortium had conducted 10,000 one-on-one information sessions with Texans, and enrolled 914 people in health plans, as of Dec. 31.

“The primary mission of a navigator — it’s really not to enroll, it’s to educate and inform,” he said.

Democrats and some health care advocates are critical of the new state rules, saying they are intended to obstruct navigators’ work by adding additional costs and training requirements during the final weeks of the six-month enrollment period.

“It’s really difficult to say that it’s not a politically motivated stunt,” said Tiffany Hogue, statewide campaign coordinator for Texas Organizing Project, political advocacy group for low-income Texans that is working with government entities in Dallas, San Antonio and the Rio Grande Valley to educate Texans on the their insurance options..

The insurance department has said that “unrelated political considerations would be an inappropriate basis for the rules,” and that its intent is to broaden the pool of qualified navigators

Ask yourself if the following sounds like how public meetings are conducted in your community: The big decisions are made in closed session, and when the council or board members face a difficult challenge, they spend most of the time sniping and immersed in personal rivalries. The written agendas handed out are long, but the descriptions of what’s being discussed are too brief and legalistic to be understood. Turnout among citizens is low, unless something has made the public mad, and so many angry people show up that it’s impossible to conduct a useful meeting. And those who come to speak tend to be regulars—many of whom are nutty gadflies. (They prove the municipal wisdom that that there are two kinds of people in the world: those who don’t go to council meetings, and those who go and probably shouldn’t.)

In my experience as a reporter, meaningful conversations between citizens do sometimes take place during meetings, but this talk occurs in corners, just outside the chambers in the hallway, or in common space. I’ve learned a lot from listening to the whispers back and forth in the open space at the very back of the L.A. Council chambers. When I visited the Clovis school board last year, a few parents talked about a problem teacher as they stood in the back right corner, along a wall, out of earshot of the people sitting in front. At Santa Monica’s council meetings, many people don’t go into the council chambers—but instead sit outside and watch on video feeds so they can talk with their fellow citizens.

This is the point in the column when earnest Bay Area types jump on Twitter to tell us that they are developing cool new technologies to help citizens engage their local government online. But precious little thought has been given to how to revitalize local government meetings themselves. To unleash the untapped power of council and school board meetings—to make them about creating conversations—we must flip our priorities and redesign the spaces, so that council chambers and boardrooms are foremost places for people to gather and talk.

What does that look like? Well, it looks like Starbucks. Take out the old fixed benches and seating of your council chamber. Set up tables and chairs and nice couches. Have a bar for serving coffee and healthy snacks and maybe even beer and wine. (I’m a teetotaler, but I don’t know how an elected official could summon the courage to grapple with California cities’ outsized pension problems without a slug of Jim Beam.)

And then take the council or board members off the dais and put them in a corner of the chambers—the way you might position a piano player in a hotel lobby. They’d be miked just loud enough that anyone in the room could hear them, but not so loud as to overwhelm any conversations.

These are obviously two contrasting views about what happened to North Carolina's labor force, based on seemingly conflicting data sets. In their paper, Hagedorn and his co-authors wrote, "We could not establish the reasons for this discrepancy based on our conversations with the BLS." So it's very possible that the data's just noisy, and it's too soon to draw any broad conclusions from a half year's worth of data in a single state.

This does, however, touch on a long-standing economic discussion about the effect of unemployment insurance. Let's rehash that debate a bit for context.

The view that extended jobless benefits are helpful during a recession. One mainstream view is that cutting unemployment benefits during a recession doesn't actually spur people to find jobs. After all, jobs have been very scarce these past few years. Even today, there are still three workers seeking work for every one job opening. People can't find jobs if there aren't jobs to be found.

That's why many economists think that unemployment insurance isn't really discouraging workers from getting jobs right now. For instance, the University of California, Berkeley's Jesse Rothstein has estimated that the expansion of jobless benefits only added 0.1 to 0.5 percentage points to the unemployment rate in 2010. JPMorgan's Michael Feroli has helpfully rounded up a variety of studies that come to a similar conclusion

Those studies imply that workers won't magically find jobs if their unemployment insurance gets cut. Instead, many workers may stop looking for work — since they no longer have to keep search to qualify for benefits. The BLS numbers on North Carolina seem to support this story.

The view that jobless benefits are causing problems. Hagedorn, however, has dissented from this mainstream view. In October, he released a paper (pdf) with three co-authors suggesting that the expanded unemployment insurance program was actually responsible for much of the rise in joblessness during the Recession. Importantly, that paper doesn't argue that jobless benefits discourage workers from looking for jobs. (They find that this effect is small, just like Rothstein did.) Instead, his model suggested that the unemployment program raised costs for employers, who saw a drop in profits and, in turn, are less likely to offer jobs.

By extension, this paper suggests that cutting unemployment insurance might be a good thing — it would boost incentives for hiring. The Census's establishment survey numbers on North Carolina seem to support this story.

Others remain skeptical of Hagedorn's argument. As Chad Stone of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities explained in this critique last fall, the paper relies on a very different model of how the U.S. economy acts during the recession — namely, one in which insufficient demand from consumers for goods and services isn't the economy's main problem. Stone argues that this model gets cause and effect backwards: Businesses aren't hiring because there's not enough consumer demand, which is why we had extended jobless benefits. Not the other way around.

So what happened in North Carolina? As it turns out, the data is still fairly ambiguous and there are two conflicting interpretations here:

1) Many workers may have dropped out of the labor force. Everyone agrees that North Carolina's unemployment rate kept dropping, much as it did in the rest of the country, after benefits got cut.

But that might have been a bad omen: According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of people in the labor force has plummeted in North Carolina since last summer (even as it rebounded slightly in the rest of the nations).

. . . some people who saw their jobless benefits lapse may well have found jobs — perhaps they decided to take a lower-paying gig than they otherwise would have, out of desperation. But a greater number of workers appeared to have simply given up looking altogether, possibly because jobs are still extremely difficult to come by, and they no longer have to keep searching to qualify for benefits.

2) ...or perhaps employment actually increased. Yet other data sets seem to tell a different tale. A more optimistic view of what happened in North Carolina comes from a new paper (pdf) led by Marcus Hagedorn of the University of Oslo. He and his three co-authors sifted through the Census Bureau's "household survey" and the "establishment survey" for the same period. And the results were striking.

What they found is that overall employment has actually gone up in North Carolina since benefits got cut in June of 2013. The household survey in particular showed a big increase in both employment and labor force participation. But both surveys suggested that North Carolina's labor force is growing, not shrinking.

Hagedorn's paper suggests that, by and large, workers in North Carolina do seem to be finding jobs ever since unemployment insurance got cut. And it's not clear that these are lesser jobs or lower-paying jobs: The data suggests that overall hours in North Carolina went up, and there was little change in wages and earnings.

The second school funding trial began Tuesday with this basic argument from the attorneys representing the more than 600 school districts in the state suing the Texas Legislature: Despite the $3.9 billion the lawmakers restored to public education funding in last year’s session, the same old problems continue because of inequitable funding.

“Nothing has changed,” argued David Hinojosa, lead school finance attorney for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, or MALDEF. The San Antonio-based organization represents some of the property-tax poorest districts in the state and a group of parents, including two from Amarillo.

The system is also inefficient because it is not producing results, Hinojosa and other attorneys told State District Judge John Dietz.

But Texas Assistant Attorney General Shelly Dahlberg countered that the funding of the public education system is constitutional.

In last year’s session, when the Legislature restored most of the funding cuts made in the 2011 session when the lawmakers tackled a $27 billion shortfall, the state narrowed the funding gap in the overwhelming majority of all school districts, Dahlberg told Dietz.

“The Legislature also improved the equity of the system,” she said in reference to one of the key arguments the plaintiffs used when they sued the state two years ago.

With the Texas school finance trial reopening Tuesday, state district court Judge John Dietz is set to consider how changes made during the 2013 legislative session could affect his February ruling that the state has underfunded its public schools.

Attorneys for the state will spend the next four weeks arguing that new high school graduation requirements and the $3.4 billion lawmakers added back to the public education budget in 2013 should change his mind. But the most prominent player in the state’s defense of the lawsuit could remain outside the courtroom, where the trial has become a political football in the state’s heated 2014 gubernatorial contest.

The leading Republican candidate for governor, Greg Abbott, is also the state’s attorney general. His office is responsible for the state’s defense against the more than two-thirds of Texas school districts that are suing over what they say is an inadequate and unfair funding system in a case that is expected to travel to the state Supreme Court.

He said last week that he does not plan to appear in court during the latest hearings. That has not stopped his expected Democratic opponent, Wendy Davis, from lobbing attacks based on his role in the litigation. Davis, a Fort Worth state senator, has her own connection to the school finance lawsuit. In 2011, she filibustered the 2011 budget bill that enacted the $5.4 billion in cuts that led to the litigation that arose two summers ago.

Rarely a fan of Washington's oversight, Texas appears destined for another clash with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency over greenhouse gas limits — this time, for existing power plants.

The rules, which President Obama has instructed the EPA to propose by June 2015, have only been suggested, but Texas regulators have already weighed in. Their opinion? The idea, though still scant on details, is no good.

That’s according to a letter written by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the Public Utility Commission of Texas. The letter, sent to EPA administrators after the agency asked for feedback, outlines several concerns, including those about the federal rule-making process, but it also touches on a hot-button issue in Austin: electric reliability.

Texas regulators say they fear that new regulations would make coal production less economical, speeding up plant retirements and straining the grid.

“Generators should not be penalized for increased [greenhouse gas emissions] needed to maintain system reliability,” the letter said. “The PUC and TCEQ urge the EPA to consider all aspects of grid reliability in developing [a greenhouse gas] rule for existing power plants.”

At issue is whether the EPA can use the Clean Air Act, which gives it the authority to regulate emissions of toxic air pollutants and to limit emissions of greenhouse gases as well. In 2007, the court had ruled in the landmark case Massachusetts v. EPA that the EPA could do so for motor vehicles, which has led to stringent fuel-efficiency requirements for cars.

But Texas, joined by states like Mississippi, Alabama and South Carolina, and industry coalitions including the American Petroleum Institute, is arguing that the Clean Air Act was never meant to apply to anything other than air pollutants, because greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane "[do] not deteriorate the quality of the air that people breathe." Attorneys representing the groups added that "carbon dioxide is virtually everywhere and in everything," and called the EPA's proposed regulations of greenhouse gases "absurd."

Of the nine petitions the group of states and industry leaders had filed to the Supreme Court regarding its challenge of climate change rules, the justices agreed to hear six, but only want to consider one question: "Whether EPA permissibly determined that its regulation of greenhouse gas emissions from new motor vehicles triggered permitting requirements under the Clean Air Act for stationary sources that emit greenhouse gases."

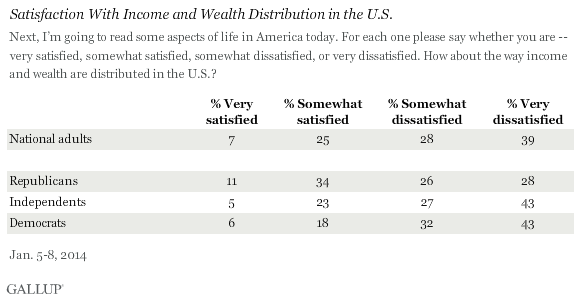

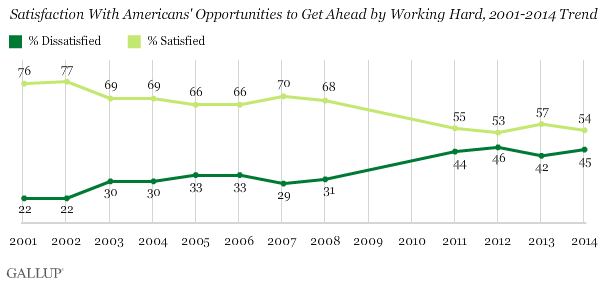

Obama will almost certainly touch on inequality in his State of the Union address on Jan. 28. This will certainly resonate in a general sense with the majority of Americans who are dissatisfied with income and wealth distribution in the U.S. today. Members of the president's party agree most strongly with the president that this is an issue, but majorities of Republicans and independents are at least somewhat dissatisfied as well.

Although Americans are more likely to be satisfied with the opportunity for people to get ahead through hard work, their satisfaction is well below where it was before the economic downturn. Accordingly, improvement in the U.S. economy could bring Americans' views back to pre-recession levels.

It’s not just contributions that the officeholders are seeking. Many also are eager for association with an industry that — while clearly as self-serving about its economic interests as any other — projects an aura of glamour and new-economy dynamism that the typical Washington pol, to put it mildly, does not enjoy.

But raising money from high tech is an art form of its own, requiring special techniques for finding the erogenous zones of rich people who tend to take themselves and their ideas very seriously. Tech leaders see Silicon Valley not just as a special place, but as unique — almost a nation within a nation that drives innovation, economic growth and the very way Americans live their lives. So capital lawmakers who don’t come prepared risk confirming the typical tech industry view of Washington politicians as clueless buffoons.

Here, based on interviews with tech political players in Washington and the West Coast, is a user’s guide for how candidates can loosen the wallets of technology tycoons.

Any evening on Capitol Hill there is a familiar ritual: A lawmaker stops by an event, gives a little speech and goes home with campaign checks. This simply won’t work for reaping tech dollars.

Just look at what happened to former Sen. Olympia Snowe. The Maine Republican sat on the powerful Commerce and Finance committees — both key for the tech industry. But during one Silicon Valley swing, she didn’t convince tech execs she cared for their industry or understood their policy desires, according to a technology source. Her perfunctory effort drew equally perfunctory results, yielding only about $20,000.

Snowe knew one thing — that most big players expect the politician to come to them — visiting with tech players in their native habitat. But what’s even harder for many pols: The tech money players usually want to do at least as much talking as the politicians. They insist on knowing that the politicians are really listening. As a general rule, the first meeting is not the right time to ask for money.

“Lesson One: We’re old-fashioned; we don’t like to kiss on the first date,” said Carl Guardino of the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, a tech industry advocacy organization. “Prove that you care about our policy before reaching for our purse. I find that all too often, members of Congress treat Silicon Valley like an ATM machine and expect to come out here without establishing themselves on our policy, without building personal relationships, and simply want to reach into our purse. And that rarely works, and it certainly doesn’t work more than once.”

Our model predicts that most workers in transportation and logistics occupations, together with the bulk of office and administrative support workers, and labour in production occupations, are at risk. These findings are consistent with recent technological developments documented in the literature. More surprisingly, we find that a substantial share of employment in service occupations, where most US job growth has occurred over the past decades (Autor and Dorn, 2013), are highly susceptible to computerisation. Additional support for this finding is provided by the recent growth in the market for service robots (MGI, 2013) and the gradually diminishment of the comparative advantage of human labour in tasks involving mobility and dexterity (Robotics-VO, 2013).

Finally, we provide evidence that wages and educational attainment exhibit a strong negative relationship with the probability of computerisation. We note that this finding implies a discontinuity between the nineteenth, twentieth and the twenty-first century, in the impact of capital deepening on the relative demand for skilled labour. While nineteenth century manufacturing technologies largely substituted for skilled labour through the simplification of tasks (Braver-man, 1974; Hounshell, 1985; James and Skinner, 1985; Goldin and Katz, 1998), the Computer Revolution of the twentieth century caused a hollowing-out of middle-income jobs (Goos,et al., 2009; Autor and Dorn, 2013). Our model predicts a truncation in the current trend towards labour market polarisation, with computerisation being principally confined to low-skill and low-wage occupations. Our findings thus imply that as technology races ahead, low-skill workers will reallocate to tasks that are non-susceptible to computerisation – i.e. , tasks requiring creative and social intelligence. For workers to win the race, however, they will have to acquire creative and social skills.

Much can be—and has been—written about the shortcomings of the WASPocracy. As a class, it was exclusionary and hence tolerant of social prejudice, if not often downright snobbish. Tradition-minded, it tended to be dead to innovation and social change. Imagination wasn't high on its list of admired qualities.

Yet the WASP elite had dignity and an impressive sense of social responsibility. In a 1990 book called "The Way of the Wasp," Richard Brookhiser held that the chief WASP qualities were "success depending on industry; use giving industry its task; civic-mindedness placing obligations on success, and antisensuality setting limits to the enjoyment of it; conscience watching over everything."

Under WASP hegemony, corruption, scandal and incompetence in high places weren't, as now, regular features of public life. Under WASP rule, stability, solidity, gravity and a certain weight and aura of seriousness suffused public life. As a ruling class, today's new meritocracy has failed to provide the positive qualities that older generations of WASPs provided.

Meritocracy is leadership thought to be based on men and women who have earned their way not through the privileges of birth but by merit. La carrière ouverte aux talents:Careers open to the talented, is what Napoleon Bonaparte promised, and it is what any meritocratic system is supposed to provide.

The U.S. now fancies itself under a meritocratic system, through which the highest jobs are open to the most talented people, no matter their lineage or social background. And so it might seem, when one considers that our 42nd president, Bill Clinton, came from a broken home in a backwater in Arkansas, while our 44th,Barack Obama, was himself also from a broken home and biracial into the bargain. Sen. Ted Cruz, the man who leads the tea party, is the son of a Cuban émigré.

Meritocracy in America starts (and often ends) in what are thought to be the best colleges and universities. On the meritocratic climb, one's mettle is first tested by getting into these institutions—no easy task in the contemporary overcrowded scramble for admission. Then, of course, one must do well within them. In England, it was once said that Waterloo and the empire were built on the playing fields of Eton. The current American imperium appears to have been built at the offices of the Educational Testing Service, which administers the SATs.

. . . What our new meritocrats have failed to evince—and what the older WASP generation prided itself on—is character and the ability to put the well-being of the nation before their own. Character embodied in honorable action is at the heart of the novels and stories of Louis Auchincloss, America's last unembarrassedly WASP writer. Doing the right thing, especially in the face of temptations to do otherwise, was the WASP test par excellence. Most of our meritocrats, by contrast, seem to be in business for themselves.

Trust, honor, character: The elements that have departed U.S. public life with the departure from prominence of WASP culture have not been taken up by the meritocrats. Many meritocrats who enter politics, when retired by the electorate from public life, proceed to careers in lobbying or other special-interest advocacy. University presidents no longer speak to the great issues in education but instead devote themselves to fundraising and public relations, and look to move on to the next, more prestigious university presidency.

In developed and developing countries alike we are increasingly living in a world where the lowest tax rates, the best health and education and the opportunity to influence are being given not just to the rich but also to their children.

"Without a concerted effort to tackle inequality, the cascade of privilege and of disadvantage will continue down the generations. We will soon live in a world where equality of opportunity is just a dream. In too many countries economic growth already amounts to little more than a 'winner takes all' windfall for the richest."

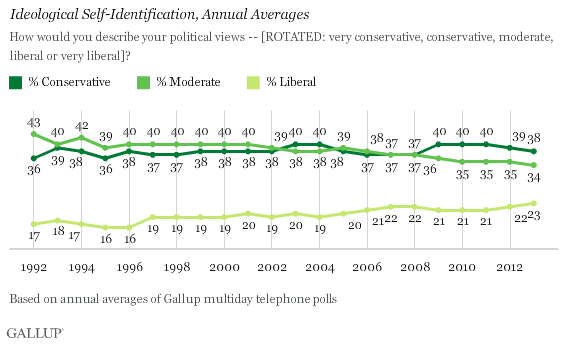

The figures are based on combined data from 13 separate Gallup polls, including interviews with more than 18,000 Americans, conducted in 2013.

When Gallup began asking about ideological identification in all its polls in 1992, an average 17% of Americans said they were liberal. That dipped to 16% in 1995 and 1996, but has gradually increased, exceeding 20% each year since 2005.

The rise in liberal identification has been accompanied by a decline in moderate identification. At 34% in 2013, it is the lowest Gallup has measured, and down nine points since 1992. Moderates had been the largest ideological group throughout the 1990s, and competed with conservatives for the top spot during the 2000s. Since 2009, conservatives have consistently been the largest U.S. ideological group.

The percentage of conservatives has always far exceeded the percentage of liberals, by as much as 22 points in 1996. With more Americans identifying as liberals in recent years, and conservative identification holding steady, the conservative advantage of 15 points ties the 2007 and 2008 gaps as the smallest.

Why has a traditionally “core subject”, which was ranked in the same academic hierarchy as English, science, and math for decades, been sidelined in thousands of American classrooms?

The shift in curriculum began in the early years of the Cold War. While U.S. military and technological innovation brought World War II to a close, it was a later use of technology--the Soviet launching of Sputnik in 1957--that historian Thomas A. Bailey called the equivalent of a “psychological Pearl Harbor” for many Americans. It created deep feelings of inadequacy and a belief that the U.S. was falling behind in developing new technology and weapons, which led to the passage of the 1958 National Defense Education Act. This legislation pumped $1 billion over four years into math and science programs in both K-12 schools and universities.

Despite this extra focus on math and science, social studies managed to make it through the end of the Cold War relatively unscathed (in fact, the number of classroom hours dedicated to teaching social studies in grades 1-4 peaked in the 1993-1994 school year at 3 hours a week). But drastic change came a decade later with the passage of President George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind legislation.

No Child Left Behind was signed into law in an attempt to address the growing achievement gap between affluent and low-income students. It was a controversial piece of legislation from the start, mainly because of its “one size fits all’” approach: It uses annual standardized tests to determine how well students are performing in reading and math and then uses those scores to determine the amounts of federal funding schools receive.

Besides the obvious criticism that low-performing schools--arguably the ones that need the most increase in funding--are disproportionally punished for their low scores, critics also believe that No Child Left Behind has narrowed the curriculum. Since the standardized tests focus exclusively on English and math, and those scores determine the bulk of a school’s federal funding, schools have been forced to increase time and resources in these subjects at the expense of all others, including social studies.